My newest massive mind critic realisation is that dystopian sci-fi settings are a intelligent approach to make fundamental (and probably tedious) components of interacting together with your game, all of a sudden thematic. “Hmmm, I’ve been clicking on this menu for a while,” You suppose. “This isn’t very interesting.” And then the display goes all crackly or no matter, and a disembodied voice materialises and says: “The year is 2483, and all humans do is click on menus. Corporations did this.”

And that’s you, sucked right into a charybdis-level whirlpool of immersion. Eyes glued to the display as you watch a textual content crawl inform the terrifying story of company goons going round with massive buckets of glue and sticking everybody’s eyes to screens….perpetually. Cyberpunk, eh? Cyberpunk certainly, says Conglomerate 451. It sits someplace between the Ultima Underworld homage of Legend of Grimrock, the debuff-firing flip primarily based fight of Darkest Dungeon, and the bottom and squad administration of Alien Defence Squad Trouser And Hairdo Customisation Adventure 2012, which I consider you proles name XCOM.

As a set of methods, Conglomerate 451 does some nifty issues. There’s an enormous quantity of consideration given to customisation and fight. As an RPG, nonetheless, it doesn’t do sufficient with its setting to take care of any actual sense of pressure or intrigue.

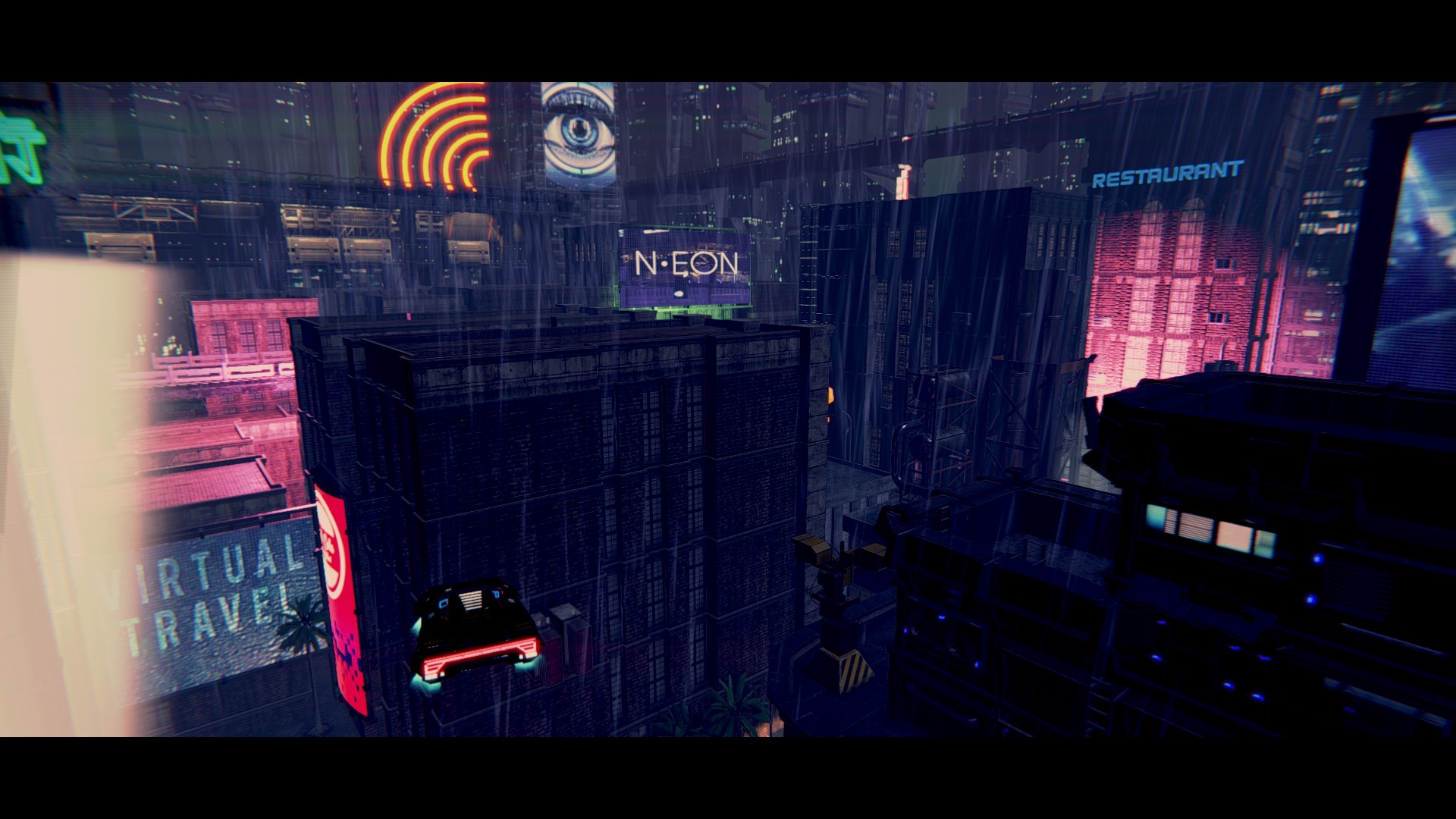

There’s some enjoyable writing, delivered through satirical information broadcasts and random occasions, however they’re all too disconnected from all the things else to make the game as a complete work as a darkish comedy. Neither does it work as commentary, except you contemplate the statement that power drinks exist, and are marketed, to be biting social satire. It’s cyberpunk as a borrowed aesthetic, relatively than as a setting. Steve Hogarty known as it ‘endless cold, wet concrete’ in his premature evaluation, and I’d are inclined to agree. Only somebody’s additionally dropped a milkshake or one thing, as a result of I like my metaphors to be unwieldy and unnecessarily detailed.

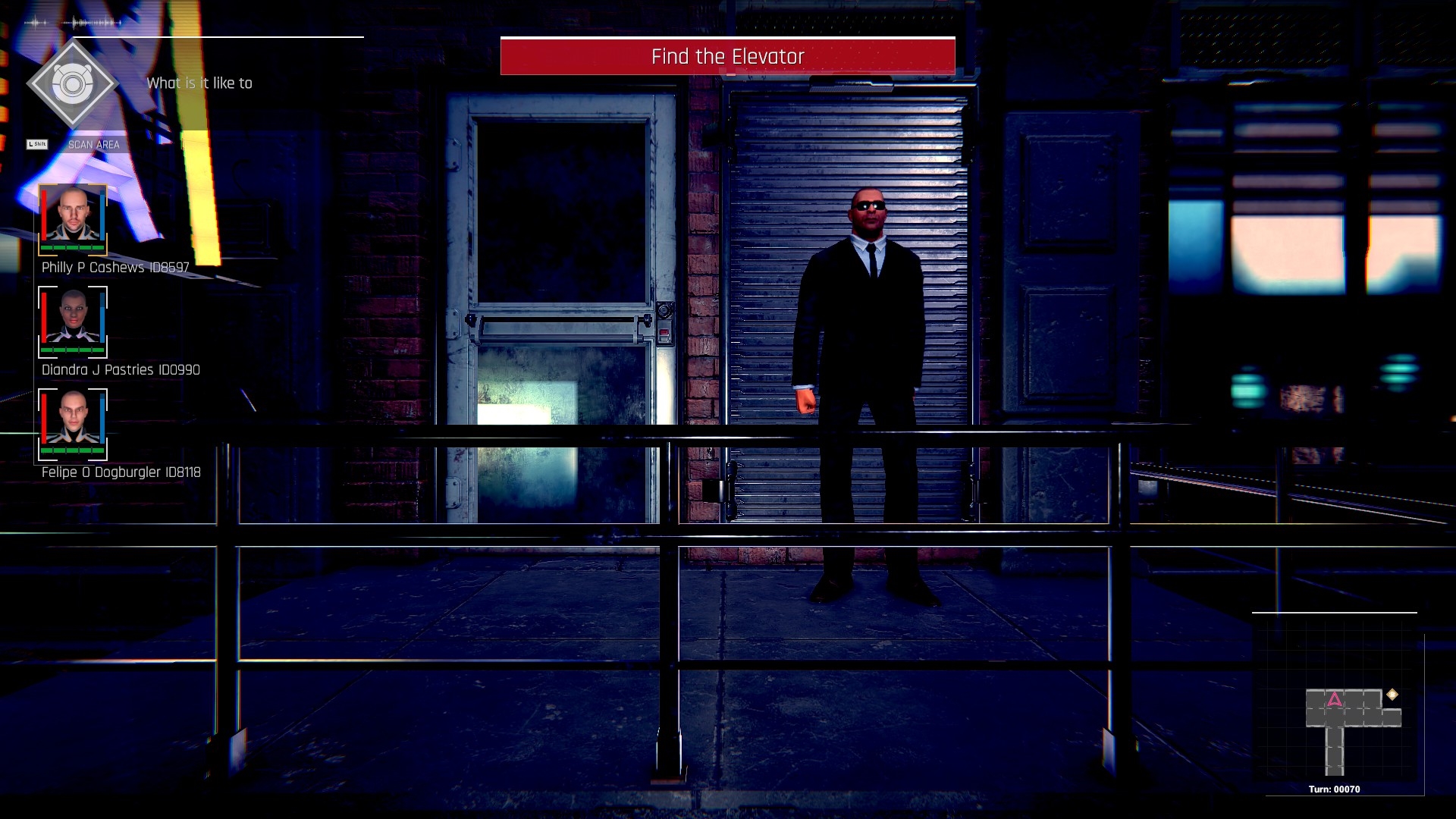

With a squad of three customised clone troopers, you discover cyberpunk-themed dungeridoos via tile-by-tile first particular person motion. You shoot canines with weapons strapped to their shoulders. You combat-hack massive lads with weapons strapped to their shoulders. You cyber-kick cyborg samurai with no weapons on their shoulders, presumably to make room for the crushing weight of style conference.

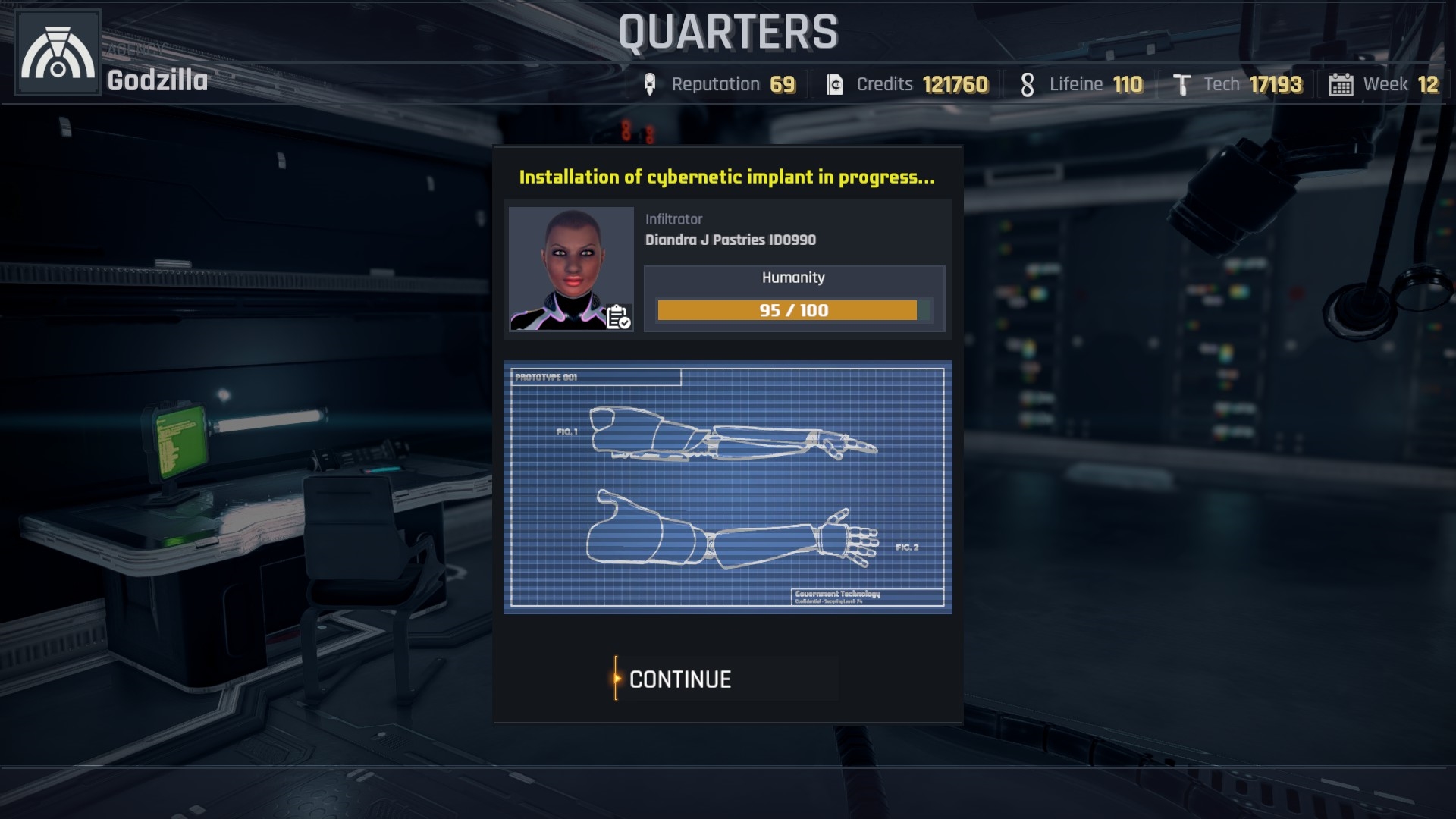

You full a “find thing/kill thing” goal. You get cash, expertise, analysis factors, and normally a number of stat-boosting implants. You return to your base-menu. You set up some implants, perform a little research, possibly clone a brand new squad member, improve a weapon, eat a pleasant plate of cyber biscuits. Then you go and do all of it once more. In story mode, you’re given a set period of time to cut back the affect of 4 firms by finishing missions. There’s additionally limitless mode, the veracity of whose identify I can not confirm, however be at liberty to ask me once more on the finish of time itself.

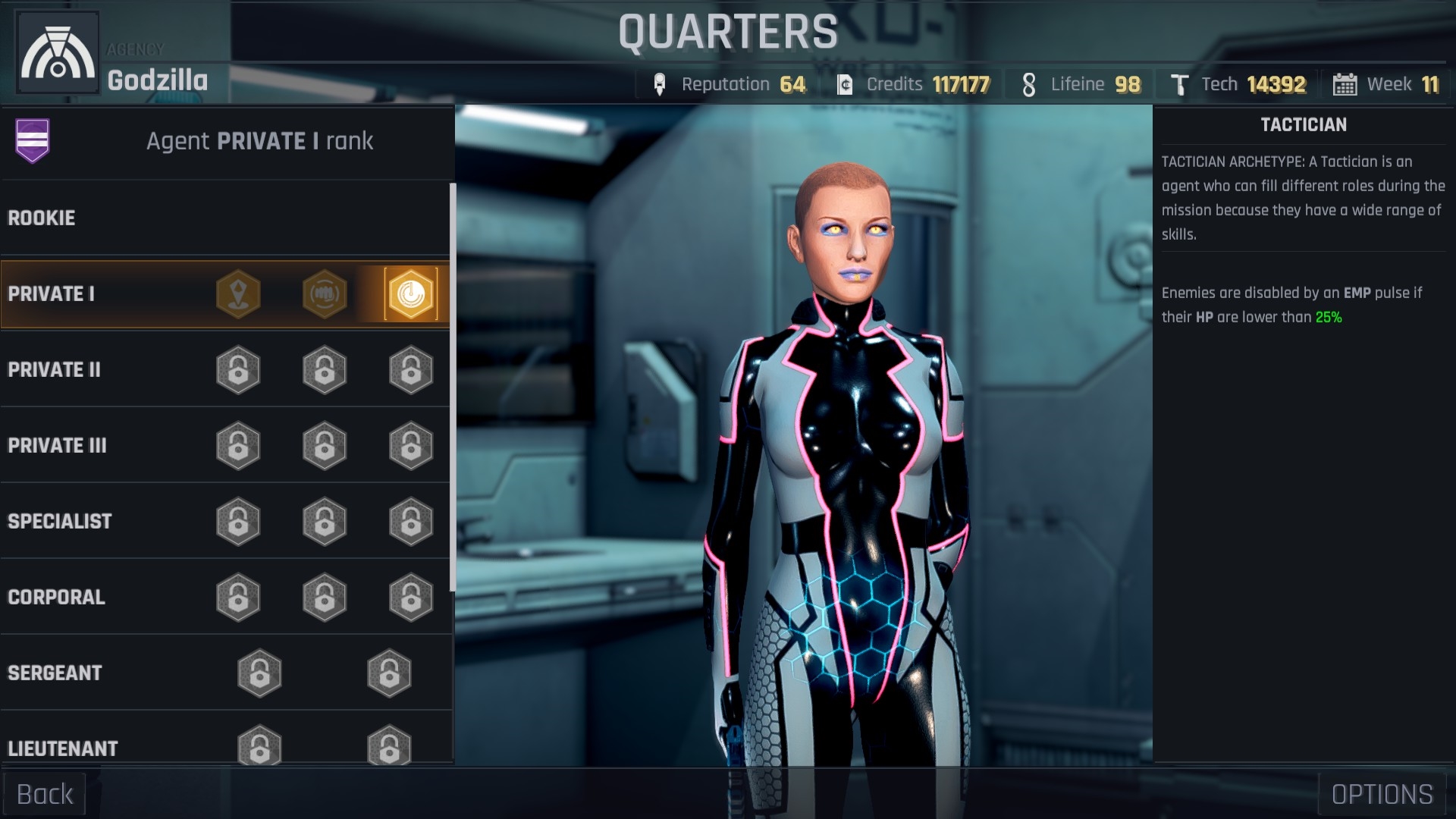

As I stated up high, there’s a number of concepts right here – largely associated to fight – that I discovered to be genuinely nifty. There’s an enormous quantity of customisation accessible in your squad members, for instance. You can unlock and apply one thing like a dozen totally different genetic mutations earlier than you even clone your soldier, every providing numerous stat bonuses. Then there’s eight totally different fight roles, from the hack-friendly techie, to the substance-guzzling juicer. There are 4 totally different cybernetic limbs to unlock and apply, plus shields and weapons to improve and add collectible buffs to. And on high of all this, every soldier has the power to hack enemies throughout fight, inflicting numerous debuffs, which you additionally gather as gadgets from cyberpunk treasure chests on missions.

Alongside this are numerous interactions between squad members and skills. So, say I resolve to clone a tanky character. Let’s name him Philly P Cashews. I give him some implants to buff up his well being, and a capability that permits him to take harm rather than one other character. Then, I spend some analysis credit I hacked from a locker within the final mission, to unlock a passive buff that provides my entire squad a defence bonus every time Mr Cashews takes harm. “That’s synergy, right there!” I shout, banging my meaty fists in opposition to my workplace desk. “That’s the kind of synergy we’ll have to survive on this chilly, darkish future the place an power drink might simply… fucking… promote itself to you at any second.

As I stated, I actually loved these things. And combined in with the marginally goofy, mid-nineties arcade cupboard animations and sound results concerned in fight, it makes for snappy, compulsive encounters. The approach enemies disintegrate is very good enjoyable. There’s one thing virtually ethereally throwback-ish about the best way the entire thing appears to be like. It seems like one thing that you just’d see on a TV present after college, the place you’d cellphone in directions whereas consuming potato smiley faces. Move man left. Monch monch. Move man ahead. Zap man in torso. Have liberties siphoned by faceless company entity. Monch.

Your squad members can get traumatised, hooked on medicine, and wounded. You can discover the streets outdoors a mission location beforehand, shopping for upgrades and buffs from road distributors, or spend cash on numerous perks – comparable to the choice to ambush everybody you meet – as soon as the mission begin. There is, I’ll say it once more, a dizzying array of choices for the right way to method fight encounters.

The factor is, I’m simply not satisfied the precise fight encounters themselves warrant a lot flexibility. Both the missions, and the enemies you battle throughout them, don’t provide sufficient problem or variation to encourage you to experiment or optimise. This might properly change on the toughest setting, and in later missions, but it surely looks as if a missed alternative to supply a lot flexibility in method, whereas instructing you you can afford to brute pressure 90% of encounters with out consequence.

The maps themselves – which I’m pretty sure are procedurally generated – might do with some spicing up, too. I’d recognize some NPCs scattered about, even when they did nothing however spout a number of strains of lore, or have some private results to rummage by. I’d even accept audio diaries at this level, or blood scrawls on partitions that say “the bad thing, it happened here”.

It goes again to the game seemingly utilising cyberpunk as an aesthetic, and an excuse for computer-magic, with out actually exploring the human considerations concerned. There’s a billboard within the intro cinematic that actually simply says ‘Neon’. Another advertises ‘Hack Cola’. I don’t wish to make a joke about an AI writing a cyberpunk script for concern of falling into some kind of terrifying Rococo’s Basilisk-esque logic gap, however you get the image.

There’s an asian-themed restaurant room that pops up sometimes on the procedural maps, and it’s very cyberpunk, little doubt. But add a restaurant proprietor, that I can chat to about how he’s quick changing into out of date as a result of he can’t afford the identical noodle-making implants as all the opposite cooks, and I’d all of a sudden be much more . Without this kind of pathos, for all their neon garishness, the style stylings finally fade into the background.

So, If you’re after a tongue-implant-in-cheek tackle immersive sims of yore, there’s Starcrawlers, which I haven’t performed however Fraser Brown liked, or I’d advocate Void Bastards. It’s a game that pays homage to style conventions like hacking and exploration, however with ahead dealing with design. Rather than backwards. Then aspect to aspect. Then 90 levels to the left. Monch monch.