Wot I Think: StarCrawlers

A space dungeon crawler

StarCrawlers [official site] is a game about punks and rebels – people eking out a living on the edge of space by stealing, smuggling and doing odd jobs for the shady corporate entities that run the galaxy. It’s cyberpunk, but with the soul of Firefly and the mechanics of Eye of the Beholder. These different inspirations fit together neatly, rather than competing, resulting in a cohesive and ambitious party-based dungeon-crawler.

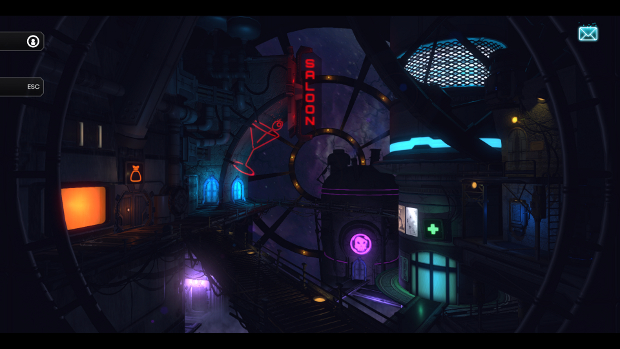

Whenever I’m perusing the job board inside the local saloon in STIX, the game’s hub, I think about Clerks. Specifically, I think about debate around the contractors working on the Death Star when it’s destroyed by the Rebels. “Speaking as a roofer, a roofer’s personal politics comes into play heavily when choosing jobs,” a customer interjects. So does a smuggler’s. At least this one’s.

See, quests in StarCrawlers are not glory-filled adventures where villagers are helped and big bads are slain. They are generally illegal, morally questionable, and tend to favour nasty corporations while screwing over their competitors. This means that almost every job you do is going to piss someone off, at least a little bit. And a Crawlers rep is their most important resource. It translates into new weapons and armour, information, help with avoiding the wrath of enemy corps – all purchased with favours earned from jobs or hostile acts against the competition.

The games of one-upmanship being played by the corps and the groups seeking to loosen their grip on humanity paint a vivid picture of the galaxy, with minimal exposition getting in the way. Though the story is fat with conspiracies, politics and revolution, it’s all told simply, and the game never loses itself in its attempt to construct an interesting galaxy. There’s only ever a few lines of dialogue between you and your next morally questionable adventure.

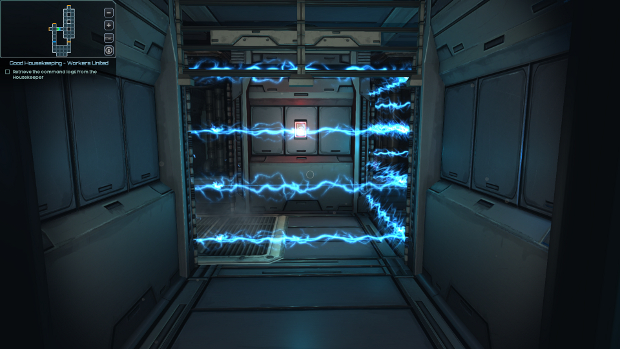

Mid-mission, there are even more ways to make new friends and foes. The grid-based dungeons are labs, offices and spaceships full of terminals to hack and lockers to break into, and along with loot, you might find secret documents or fancy prototypes. Special finds can be sold at auction back at STIX for money, rep and items, but some can also be sent directly to a specific corp for a big payday. All of these things affect a Crawler team’s standing, and also necessitates a team that can get into those hard to reach places.

StarCrawlers classes are an eclectic bunch, featuring sci-fi mainstays like Hackers and Engineers, along with more unusual ones, like the Force and Void Psykers – essentially the game’s magic users. Each has their own personality, as well as exploration and dialogue skills that unlock extra options, like hacking terminals or fiddling with people’s minds. They’re all helpful, though the Hacker’s abilities see far more use than the others. Unless a room is completely empty, the hacker probably has some work to do. Thankfully, there’s no hacking mini-game, just a dialogue box and, sometimes, a few different options on how to proceed. The rest is left up to RNG.

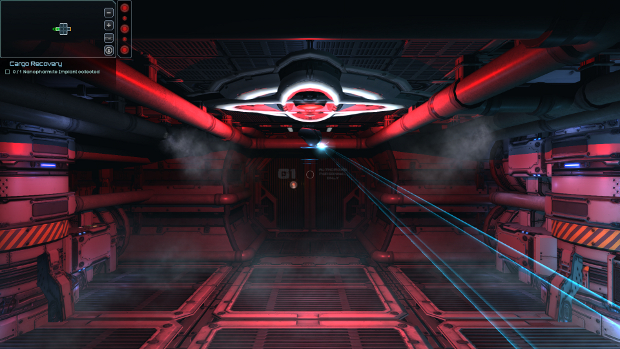

Expect to spend more time fighting than exploring and looting, however. Rare is the door that doesn’t hide an enemy on the other side. Robotic waiters, medical bots, horrible alien beasties and scimitar-waving pirates are just a few of the angry things waiting to murder your team of four rogues. They’re an odd bunch too, their designs skewing towards cartoony. Security bots lob orange cones, insane medical drops chuck toxic syringes – StarCrawlers is a bit wackier than your average gloomy cyberpunk setting.

Unfortunately, the vast majority of these peculiar threats are very bad at the whole murdering thing. Aside from the visual diversity, there aren’t many differences between them. A challenging enemy is usually just a damage sponge, not an opponent with surprising or tricky abilities. Yet I enjoy the scraps in StarCrawlers a great deal. It’s all down to the Crawlers themselves, as each is blessed with three very distinct ability trees and, even more importantly, wrinkles that make using these abilities risky.

Take the Void Psyker, for instance. They’re big fans of Cthulhu, for some reason, and use dark magic to harm enemies over time. Their big attacks require void energy, which can be generated by lesser abilities. However, void energy is exceptionally dangerous to just about everyone, including the Void Psyker. Once their meter fills up, there’s a chance that the energy will erupt out of them, making them faint while harming everyone in the room.

Time is another resource that demands attention. Every ability has a specific number of units of time attached to it. The higher the number, the further back in the order of attack the character will be placed once it uses the ability. So a powerful or charged ability might force a character to wait for everyone else to get two turns, while a basic attack could be used twice in a row, potentially. It’s the system rather than the foes that require tactical thinking to overcome.

Engaging though battles may be, there’s still just a little too much combat. With the countless side missions and the optional but recommended grinding for loot and experience, there’s no end to the fighting, and by the halfway mark, it starts to lose steam. There are too many of the same fights that are a foregone conclusion. Objectives suffer similarly, but they start repeating right from the get-go.

Main missions fare better, though. They’re hand-crafted, so the dungeons tend to be more elaborate, and usually contain extra objectives and optional paths. And there’s the story driving them forward, a space yarn with its share of intrigue and rebellion. Like the side missions, however, it’s still very much tied to reputation and the squabbles of corporations.

I’ve found myself treating StarCrawlers like a game with a morality system, despite the absence of one. That’s not what the rep system is, but for me it serves the same purpose. Sure, sometimes I do jobs just to make ends meet, but whenever there’s an opportunity to help the vulnerable, especially when it cost the corps something, I take it. But unlike a lot of proper morality systems, the game doesn’t assume anything. Maybe I’m still just in it for the money. Maybe I just want to watch the galaxy burn. I determine why I’m doing something, not the game.

Making the most out of reputation means going on countless runs, procedural mission after procedural mission. Quantity is a necessity, and for a small developer like Juggernaut Games, the best way to create lots of missions and ways to influence the corps is procedural generation. It’s just a shame that procedural generation is also a really good way of making everything feel far too familiar. After a dozen hours, it’s all just variants of the same dungeons over and over again.

By the time I grew a bit bored of the dungeons, however, I was already invested. So that I didn’t need to keep checking the corp information menu, I even scribbled down my grudges or the names of groups I needed to butter up in my Little Book of Debts. Even more than Syndicate or Shadowrun Returns, StarCrawlers manages to capture the essence of cyberpunk and turn it into compelling systems. Despite the concessions made in the name of ambition, it’s an impressive dungeon romp.

StarCrawlers is out now on Windows, Mac and Linux via Steam and GOG for £15/$20/€20.