I’m Nate! Animator, VFX, Simulations, and Lead Developer at Crowbar.

The limitations of trying to make a good looking game in 2020 on an engine that first came out in 2004.

I was one of the first 5 people on the team, in early 2005. Back then they had no animators at all so my mere application meant I got accepted immediately haha.

The planning did not fall primarily on me, but it was incredibly challenging for all involved. Much of the difficulty was the immovable pillars of the original Xen campaign itself. Jumping puzzles have aged very poorly in FPS games, but we’ve got this long jump module that we have to use. We have to brainstorm emergent gameplay with only like 3 enemies (headcrab, bullsquid, houndeye) that were all early-game enemies that stopped being challenging 10 campaign hours ago. We have to make non-linear and alien-feeling levels without the aid of objective markers, tooltips, cutscenes, or any of the other crutches that modern gamers are used to.

Join a mod project for a game you’re passionate about. They’re full of like-minded people just trying to have fun and make something cool. They’ll let you make mistakes and learn the skills you need while on the job.

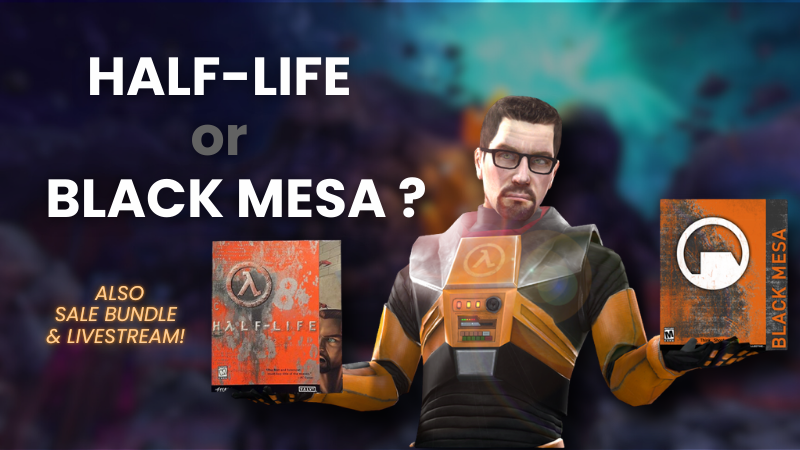

I’m very proud of the end product we shipped and don’t think there are that many areas it could have been better. But parts of the campaign could have been shortened so the whole experience was a little tighter in places. It’s not really an issue compared to so many modern games that pad their campaigns with pointless stuff, but just in further pursuit of a perfect FPS, there are sections of Black Mesa where you’re kinda thinking “how much longer until this part is done?”

The Source engine had several limitations that made it very difficult to get the types of animations the Xen campaign demanded. In any game engine, most movement is controlled by “bones”. That’s easy to visualize with a character like a human that anatomically has a skeleton, but bones are also controlling the pieces of a building as it blows up, or the pulsing of a protozoa membrane in Xen. With regards to bones, Source does not support “bone scaling”, it has a 128 bone limit per model, and each vertex in the model is only allowed to be influenced by 3 bones. These are all limitations that modern game engines do not have and it caused a lot of headaches. Many of the bigger destruction models were split into 5-10 “parts” and reassembled back together in Hammer to get around that 128 bone limit. When you’re dealing with something like a barrel cactus swelling up to a huge balloon and bursting, that should be just a couple of bones being scaled up. But Source can’t do that, which means you need “point clouds” of bones all over the model moving outwards to achieve the same effect. Only 3 influences per bone also meant those bone clouds had to be pretty dense or else you would get jagged deformations instead of smooth. I had to develop all sorts of strange pipelines to work around these limits.

I’d love to see a game with the crazy weapons and enemy types of Painkiller combined with the intricate level design of Half-Life. I also think technology is at the point where, with a little engine resource re-allocation and gated level design, we don’t need to have disappearing corpses, we can use bodies and gore as part of the gameplay loop.

That was the result of several inside jokes. There was an application we got early on in development that was over-the-top ridiculous (we later found out it was submitted as a joke). And we started imagining how this applicant might dress himself, and one of the artists whipped up this purple hat. Our Level Designers love to cram their maps full of easter eggs, and then Half-Life 2 Episode 2 with the gnome run gave them the idea to do a hat run.

Oh, lots. Anytime a good FPS game came out in the last 10 years we’d be like “oh we need X, Y, and Z in Black Mesa!” For the Xen campaign, probably DOOM 2016 was the strongest influence in terms of how to craft cool boss encounters, and lots of sprawling vertical levels with minimal navigation hints (though they did have objective markers like everybody else these days).

We knew that our Xen was going to be dramatically different from Valve’s, and in turn both of our versions dramatically different from what Laidlaw originally envisioned. Comparing Half-Life Alyx and Half-Life 1, you can pretty much see how that’s the same artistic vision, despite a 20-year graphics jump. But Half-Life 1 to Black Mesa Xen, absent the iconic Half-Life fauna, you wouldn’t peg those to be the same universe. And we knew that. It was part of our core strategy to break from the original Xen campaign and forge our own path. We didn’t want 6 hours of green-grey levels, we wanted to experiment with distinct biomes and different color palettes, so it was an intentional choice for us.