It’s an all-too-familiar problem for humans and animals in rich countries: Overuse of antibiotics, now as accessible and affordable as band-aids, is increasing the risk of bacteria becoming dangerously resistant to the drugs.

Now it’s moving into the developing world. New data suggest antibiotic overuse isn’t limited to wealthy countries anymore: As the middle and upper classes of growing nations like India, Vietnam, Belarus, and Kenya have expanded, so too has their demand for antibiotics to sanitize meat and treat medical problems, according to a new report from the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics and Policy (CDDEP). Researchers gathered data on resistant bacteria and antibiotic use from dozens of countries, then put together exhaustive maps that reveals where the crisis is worst in the world.

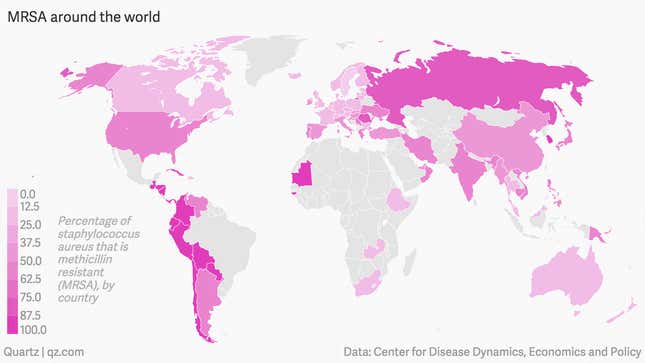

This map shows the percentage of staph infection-bacteria that are resistant to most antibiotics (or MRSA) in more than 70 countries:

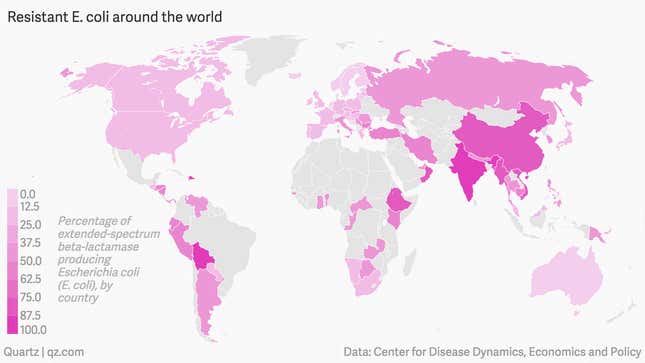

This one shows the percentage of hospital and community E. coli samples with resistance to popular antibiotics in these countries.

“The rate of increase in antibiotic use has been unprecedented,” Ramanan Laxminarayan, CDDEP’s director and one of the study’s authors, tells Quartz. “It’s truly a global problem now. And this is not a problem where we can say ‘Well, we’ll just go find another antibiotic,’ because under our system, that just makes sure drug resistance affects those new ones as well.”

When breaking down the drug-resistant bacteria in different countries, researchers found that E. coli—a bacteria found in dirty water or undercooked food—showed especially high rates of resistance in India, where antibiotics became popular relatively recently. Meanwhile, in countries like Sweden and Denmark, whose citizens have been pummeled with information about harmful antibiotic overuse, the rate of resistance is near zero.

Similar educational efforts in other countries could significantly decrease both antibiotic use and bacterial resistance, the report suggests. Laxminarayan and the other researchers emphasize that it’s more important to prevent the further development of drug-resistant than to invest in new antibiotics.

“This is not an intractable problem. It’s not impossible to deal with,” Laxminarayan tells Quartz. He adds: “Simply investing in new antibiotics is likely to result in expensive drugs that are, down the road, out of reach for many in the developing world where antibiotics are most needed.”