Photo by: Photo by Timothy Saccenti

Danny Brown is a sound archivist, compiling offbeat samples from across time and preserving them as the bedrock of his mad scientist take on hip-hop. Since 2011, he has been at the forefront of rap experimentation while remaining uniquely in tune with the genre’s roots, unifying classicists and progressives alike. His 2011 breakthrough, XXX, carried in it his tumultuous past, one riddled with drug use and distribution in his hometown of Detroit. He subsequently became a poster boy for zonked-out party rap, a role often at odds with his reality and his anxieties.

The 35-year-old Brown, a late-bloomer, has had a career paved with misfortunes, arrests, and industry machinations. He spent the first half of his 30s making up for time lost to prisons and label executives in his 20s, rewriting the rules of what it means to have a successful rap career. His new album, Atrocity Exhibition, is meant as a sequel to XXX, a living document of an eventful chapter in his life, with influences ranging from Joy Division, Raekwon, Björk, Talking Heads, and more. He is constantly using different artists, albums, and songs as reference points in his life, as he explains below, recalling the sounds that molded him as a musician and a man, five years at a time.

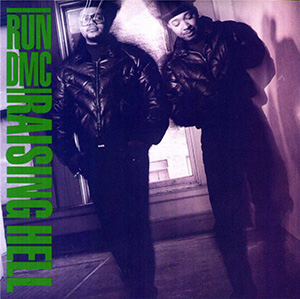

Run-D.M.C.: Raising Hell

Around 1986, this was the album everybody was listening to everywhere you went. You couldn’t escape it. And it didn’t sound like nothing else. I’d heard rap music before that, but this was real minimal, raw, and in-your-face. I remember my family barbecuing and playing Raising Hell on the Fourth of July—when it came on, I stopped playing with the other kids and just sat there and listened to that album, back and forth, back and forth, flipping the tape over. I almost knew the entire thing by the time that day was over.

Subconsciously, it [had an impact on the way I make music] because it taught me how to have an open mind, with them working with Aerosmith and everything. They was already crossing genres before I even thought about it. And they weren’t even being experimental like that because they didn’t even know what they was doing—they was just going with they heart and they ears. In some sense, Raising Hell was like my introduction to rock music.

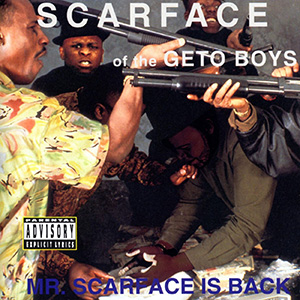

Scarface: Mr. Scarface Is Back

I was just starting to write and rap then, in the fifth grade. And that’s when I heard Mr. Scarface Is Back for the first time. It scared the shit out of me. I’d never heard music that struck that emotion in me. He rapped with such conviction. I didn’t have no choice but to believe him. It was almost like a preacher type of thing; like he had a sermon going. My cousin had the Geto Boys album, too, but that didn’t strike me that same way as when I first heard the song “Mr. Scarface.” It had the Scarface sample on there and the beat was so crazy. It was shock value to me. It was like, What is this guy talking about?!

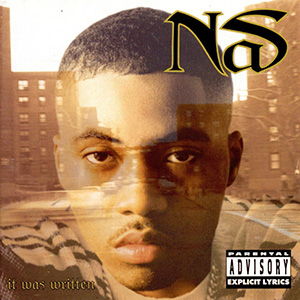

Nas: It Was Written

’96 was one of the biggest years for me, especially becoming a rapper. I actually had a job at the time, which was rare; I didn’t really work jobs. But I lied on this application at this buffet—I was 14, but you’re supposed to be 16 to work in Michigan. I’d been working there for about a year when Nas’ It Was Written came out. I was already a super Nas fan: trying to dress like Nas, had my hair cut like him. I had to go to work the day it came out, but I remember buying the album at the mall and going back home and listening to it and just instantly saying: fuck work. I called in and they was like, “If you don’t come to work you getting fired,” and I was just like, “Well, fuck it then, I’m getting fired.” I lost that job to stay home and listen to Nas. It was the best decision I made in my life. That day, just sitting at the house listening to that album, made me say, Fuck everything—I’m going full-fledged with this rap thing.

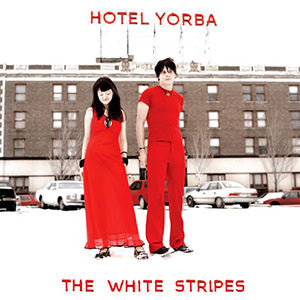

The White Stripes: “Hotel Yorba”

I went to this spot in Detroit called The Old Miami and saw the White Stripes play there, and you could tell home people was dick-riding them! They was treating them like celebrities. I was wondering why people was acting like that, because I went there to see bands play all the time and I didn’t know about them. I lived in the neighborhood and I would just go hang out there and try to pick up girls and shit. Listening to the music, I couldn’t get into it at first, but then I heard “Hotel Yorba,” and I was like, “Fuck, this is so good.” On that one you could more get into the lyrics and the song because the drums wasn’t so loud and going crazy. I fell in love with them right there. And next thing I know they was on MTV. It changed my life in that sense of knowing that I seen these guys play in a dive bar in Detroit and now they on MTV and they was winning Grammys after that. They really gave me that inspiration that I could do it on my own terms.

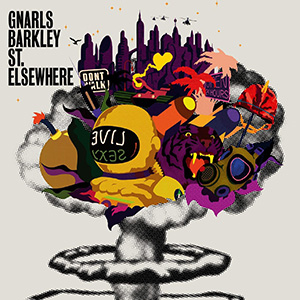

Gnarls Barkley: St. Elsewhere

I was in New York making mixtapes and trying to get my stuff going in 2006. It was a hard time in my life. I was going through a lot of shit. I wasn’t where I wanted to be. I was fucking poor. And because I was so depressed and going through shit, the album that really sticks out to me was Gnarls Barkley’s St. Elsewhere. That’s a classic to me. It helped me out. I went to jail like not too long after that, and that Gnarls Barkley shit was in my head all the time. I sang [The Odd Couple’s] “Who’s Gonna Save My Soul” to myself and was really feeling like that. Imagine singing that to yourself in jail. I was really going through it, man. That’s not an easy time to relive.

Around then I was really getting into Dilla, too, starting to respect how much of a genius he was, going back and doing my homework. Before that, I knew of his work from a distance, but I was probably being a hater; I wasn’t into Detroit rappers because I was trying to get my own shit going. But I came back to it because I didn’t have a sound and I didn’t know myself musically. So the best and easiest thing to do was to adapt to my environment. And what’s the sound of Detroit: J Dilla.

At the time, [label reps] was trying to get me to do whatever was trendy. I wasn’t being able to spread my wings and be artistic. So I was like, “Fuck that, I’m gonna start rapping off these Dilla instrumentals.” That’s how [mixtape series] Detroit State of Mind came about—because I didn’t want to rap over fucking 50 Cent instrumentals.

St. Vincent: Strange Mercy

I listen to Strange Mercy a-fucking-lot. It’s so beautiful, man. She made something so fucking crazy. It’s a story to me. It’s a movie. It’s like the album’s a dominatrix. It wasn’t nasty and dirty like XXX was, but it was pretty much hitting on some of the same topics. There was some freaky, sexy-ass shit going on in that album, but you wouldn’t know that in layman’s terms—you had to dive inside of it. I liked her for that. I’m a huge fan of St. Vincent. Annie Clark’s a bad muthafucka, man.

During that time I was experimenting, too. I don’t even remember [making XXX], but I do know that I wasn’t done with it. They forced me to put it out, they took it from me. But I’m glad they took it from me because I probably would’ve fucked it up. I’ve learned that you can overdo stuff just thinking about it too hard. XXX taught me just to rap, make songs, and don’t overthink shit. I recorded that album in two days. I didn’t have a budget. I just got with my friend who was working at a studio, and he would let me come in late at night once his shift was over and we would just record until six in the morning. The first night I tried to go as far as I could, but my voice went hoarse, so the next day I came back and I finished the rest.

David Bowie: Blackstar

Blackstar is definitely the biggest album to me this year. That album is fucking creepy. It scares the shit out of me. And those videos. Fuck. I kind of relate to it, to him. When you put that much of your life into music, can’t nobody ever take that—you can’t rate that. You can’t review this. He died for this. This is his life right here. When people talk about the best albums of the year, I be like, “Y’all don’t realized Bowie’s album came out this year and he fucking died? What is y’all talking about?” We should hands-down know what the best album of this year is. Shouldn’t be talk of nothing else.