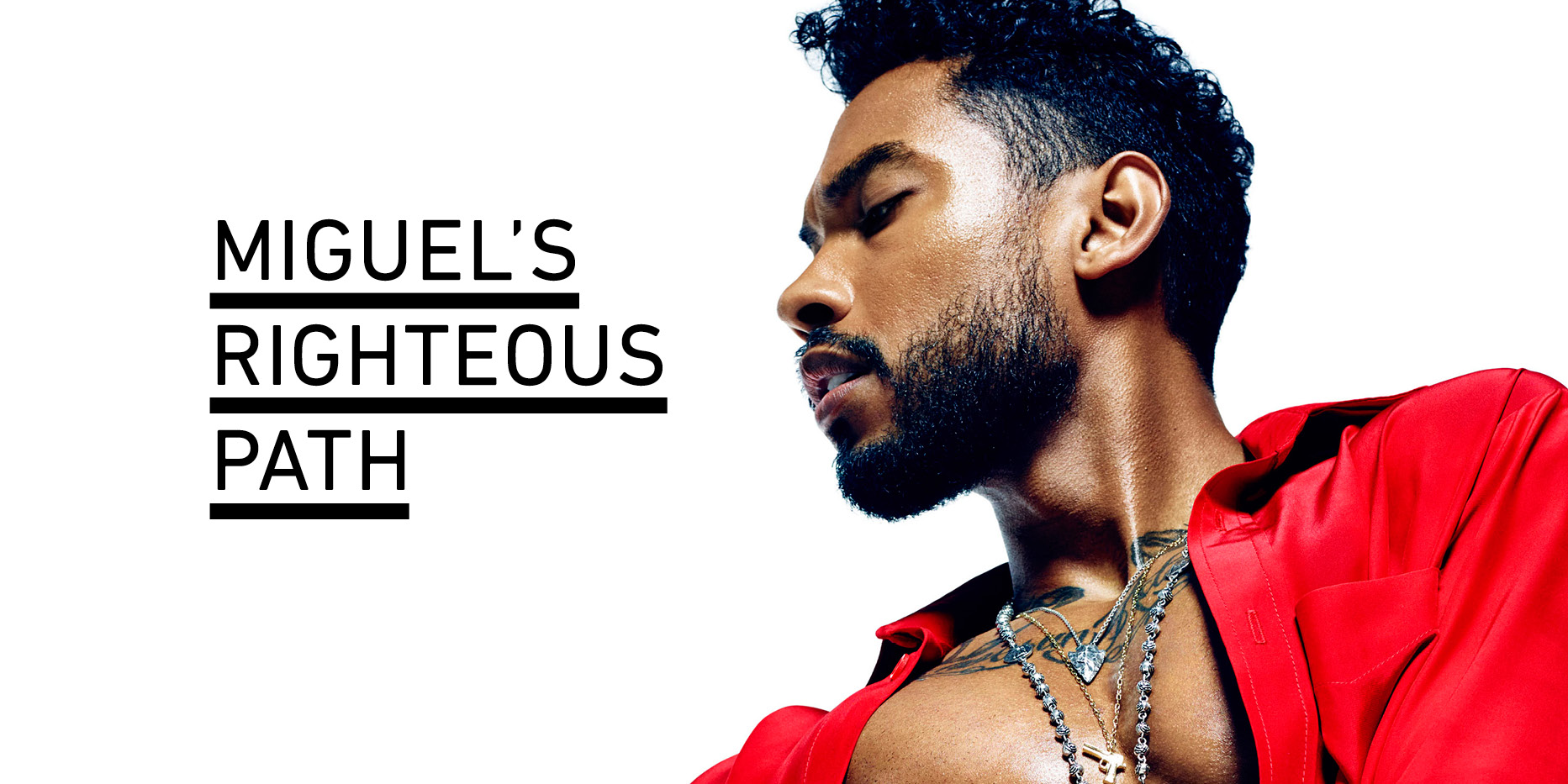

July 2, 2015 Photo by: Daniel Sannwald

I’m trying to play it cool as I call up the guy responsible for the year’s most seductive album, but my heart is pounding with the reality that I’ve almost certainly never spoken with someone who radiates sex as confidently as Miguel Pimentel. Presumably, he gets this a lot, and his presence over the phone is pure zen master—a patient, thorough thinker who rhapsodizes about his love of meditation and is fond of declaring things “righteous.”

Wildheart, the 29-year-old’s latest and best album, comes nearly three years after Kaleidoscope Dream, a record that shifted the perception of Miguel from capable hitmaker to ambitious soul auteur. When that album came out, the term “alternative R&B” was often being used to signify sounds that deviated from the perceived norm of the genre’s bump and grind. These days, there is increasingly less need to make those distinctions: Listeners are willing to accept a broader idea of what R&B can mean. It’s hard to understate Miguel’s role in this shift; he is the guy who lands vulnerable, poetic soul songs on the radio, coexisting with music that sounds very little like it. “I was one of a few people that represented music that was more soulful,” he says. “We were tired of the kitschiness and the clichés, and it’s cool to be able to represent for kids just like us, who want to hear music the way we want to hear it.”

Wildheart moves that conversation forward even more: It’s a dense, muggy, and, in parts, pointedly anti-pop record, one that seems to defiantly skirt the subject of genre entirely. If Kaleidoscope Dream tended to use sex, drugs, and rock’n’roll symbolically, applying them to tight pop singles, Wildheart is fully immersed in all of the above, though never at the expense of purposeful songwriting. A self-professed hoarder of sounds and ideas, he references musical touchstones that bubbled up from his Los Angeles childhood and into the record: Bowie, Queen, the Beatles, the Stones, Phil Collins, Hall and Oates, Miles Davis, Smokey Robinson.

And while much of the early response has centered around the album’s obvious carnality, a focus on straight-up fucking paints an incomplete picture of Wildheart’s themes. Yes, there are the id-driven sex jams like “The Valley”—“I’m your pastor, baby/ Confess your sins to me while you masturbate”—but more often, there are moments of pure intimacy that color even his freakiest tales. “Comfortability is underrated,” he says as we talk about “Coffee”, the record’s radiant lead single, which zeroes in on morning-after bliss. “It takes the ego out.”

Miguel is sure with his words, describing his most revealing work yet to me with methodical care. The only thing he can’t quite describe is his thirst to play this album live, in front of real people. Forget speaking through headphones and a screen—he wants to connect to you directly. “I can explain a lot of my experiences, like the first time I smoked weed, but I don’t know how to give someone that feeling of being onstage,” he says. “To be completely in the moment, and to be in control, and to have a tangible way of knowing what people feel about what you’re doing—it’s, like, spiritual. And that’s how you know it’s real.”

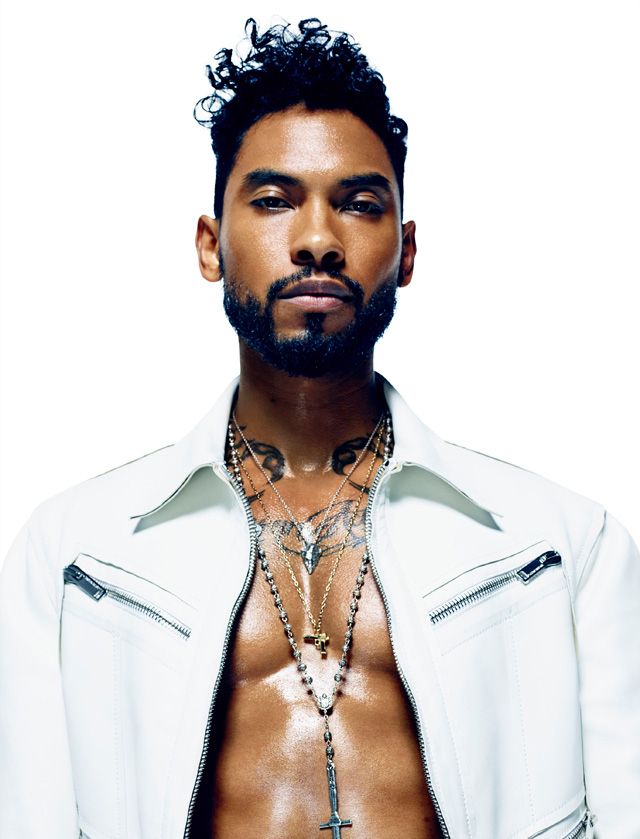

Photo by Daniel Sannwald

Pitchfork: A lot of the conversation about Wildheart has been about purely physical sex, but I hear a lot of intimacy in the album, too.

Miguel: I shroud a lot of my songs in love and lust because I know those things are relatable, and people can take them at face value, and that’s OK. But more often than not, my conversations about love and lust are directly related to my dreams. So in that sense, even when I’m singing, “I wanna fuck you like we’re filming in the Valley,” it is a little vulnerable. Because when you’re talking about your dreams, what else can you be but vulnerable?

Pitchfork: On the opposite tip, it took me by surprise to hear you lay out your insecurities in such a bare fashion on “What’s Normal Anyway”. Part of me was like: Wait, this guy feels alone?

M: In reality we all feel like an outsider in some way at some point in time. That song is an anchor in the album, because even if people listen to my music and are like, “OK cool, this is like some sex shit,” that song will bring everyone back to what the real purpose is. It’s a harness for myself, too—a reminder of why we do this shit.

Pitchfork: Being alone is underrated, too.

M: There’s something special about solitude; solitude and loneliness aren’t really synonymous. You can feel real loneliness even when you’re in a crowd, but solitude is when you feel at home, because you’re with yourself.

Pitchfork: What was your vision for the album art?

M: More than anything, I wanted to paint a picture of confidence and power, because any wild heart has freed themselves from a certain degree of care about others’ opinions—they have to!

Pitchfork: What does being a wild heart mean to you exactly?

M: It means taking the time to know yourself enough to trust your gut. Because when you know who you are and what you stand for, then you’re no longer trying to measure up your decisions with the way they’re perceived by the outside world. Other people may think you’re wild, or unconventional, or foolish, but to you it doesn’t matter, because your belief is deeper. It’s rooted. When you’re wild-hearted, you have to lose sight of yourself at times. And as rewarding as that may be, it can be misunderstood, and your path might take you in a direction where maybe other people can’t go with you. But I just don’t care to do something that doesn’t resonate with who I really am.

Pitchfork: Do you still consider yourself to be an R&B artist? Wildheart feels very much like a statement about moving past genre.

M: I just look at myself as an artist. Categories and genres are what businesses use to help put my music in the places where people can find it, but I’m not creating and thinking that way. It’s funny because, if we were going by sonics alone, then a lot of the music people are putting on pop radio right now would really be rap or R&B, but we’re actually categorized by—and I hate to say it but—ethnicity. But I just make the music I want to hear, and wherever they want to put it, that’s cool with me.

Pitchfork: Los Angeles feels like its own character on the record, what is it about that particular place that speaks to you?

M: Man, L.A. is the perfect symbol for the conversation of Wildheart, in that everywhere you go in L.A., there’s a juxtaposition of hope and desperation. So the journey of any wild heart is riddled with those two dynamics. And in the desperation, you reaffirm what you stand for, and then you have hope, faith, belief, and a more finite sense of direction. So as you move in that direction, you change, and then a new adversity becomes your desperation. It’s like a pendulum that swings from one end to the other. That’s life.