by Evan Minsker

November 20, 2015

A few years ago, a business association in Detroit decided to rebrand their neighborhood. Much of the area that used to be known as the Cass Corridor—infamous for its drug and prostitution problems—became known as Midtown. Now, according to local media, if a hip restaurant opens in the vicinity, it happens in Midtown, but if someone gets mugged in front of that restaurant, it happens in the Cass Corridor.

The old moniker wasn’t just associated with crime, though—it’s where music history was made. It was in that neighborhood where the MC5 played a set that was broadcast live on TV in 1970. Early rock’n’roll magazine Creem had an office there. It’s where the White Stripes performed for the first time, at the Gold Dollar, in 1997. So when Jack White recently announced that his Third Man Records was planning to build a Detroit hub in that very same area, at 441 West Canfield Street, the press release made no mention of Midtown.

But the stretch of Canfield where Third Man Detroit will open its doors on November 27 is far from sketchy. It’s fully developed, a sterling example of rehabilitation or gentrification, depending on who you ask. The store shares a block of real estate with Shinola, a high-end retail outlet that touts the American-made authenticity of its $800 watches while importing some of those watches’ parts. For Third Man co-founder Ben Blackwell, the new endeavor marks a return to the neighborhood where he used to sneak into shows as a teenager. It’s a homecoming—even if that home isn’t exactly how it used to be.

The soon-to-be home of Third Man Detroit. Image courtesy of Third Man Records.

White, who declined to be interviewed for this article, came up in Detroit before moving to Nashville in 2005 and then opening the inaugural Third Man store there in 2009. Last year, he said the White Stripes’ success was originally met with cynicism in Detroit and that he found it difficult to “live and create” in that environment. So while Third Man’s Nashville storefront reads “Established in Detroit”—and while White has definitely helped out his hometown in many ways, including saving its Masonic Temple—Third Man’s public persona is intrinsically linked to its Tennessee home base at this point. Every curiosity and vinyl experiment in Third Man’s catalog—the novelty wonders that defined their aesthetic—happened in Nashville. And for logistical reasons, none of the label’s three co-founders—Blackwell, White, and Ben Swank—are planning to move back to Detroit.

With so much history established in another city, the question becomes whether or not Third Man Detroit will feel pointedly secondary to the company’s Nashville headquarters. Blackwell acknowledges that concern. He says Third Man came up with a plan to do something in Detroit shortly after the Nashville store opened, but they wanted to make sure to build a Detroit presence “under the right circumstances.”

White, Blackwell, and Swank finally found those ideal conditions when they visited the space at 441 West Canfield Street back in April and noticed a big room in the back. White floated an idea: They could put Third Man’s first-ever record pressing plant in there. And now, after months of meetings all over the world and some thwarted attempts to obtain vintage pressing equipment, that’s exactly what they’re doing. Like something out of a triumphant Chrysler commercial, Third Man is bringing real-life manufacturing jobs back to Detroit.

Third Man plans to house at least eight vinyl presses at their new Detroit location.

While this news isn’t unheard of or unprecedented at large—four pressing plants have opened in the United States so far this year—Third Man’s will be the first to open in Detroit since the family-operated Archer Record Pressing started up in 1965. (Soon after Third Man hatched the idea to add record manufacturing to their business model they flat-out offered to buy Archer, but were denied.) Opening a pressing plant is a nice idea, but it takes a wealth of knowledge and something even more elusive: pressing equipment. These machines are a sought-after commodity—rare, and often in disrepair—and a recent New York Times article detailed the “global rush” to find, purchase, and restore existing presses. “It’s very hard to try to get traction in that world,” Blackwell says. “If you don’t know someone who has old presses, good luck knocking on every warehouse door in the Midwest hoping to find some.”

Eventually, Third Man got a line on some presses down in Mexico, so Blackwell flew down in June to inspect them. But the deal fell apart (and the equipment went to the Virginia-based pressing company Furnace). Then, confidentially, he told a friend about Third Man’s intentions to get into the pressing game. That’s how they came into contact with a North American sales representative for a German startup called Newbilt that’s dedicated to building new machines and refurbishing old ones. “You hear people say, ‘Nobody’s making new vinyl presses,’” Blackwell says. “But these guys are making them and they’re selling them.”

While the pressing plant won’t be operational when Third Man opens on Black Friday, they eventually plan to house at least eight working presses. A window in the shop will let customers see the manufacturing floor as part of Third Man’s ongoing initiative to educate the public about vinyl culture and show that, as Blackwell puts it, “all this stuff is alive and well.”

While the manufacturing arm definitely means that Third Man will have quick access to pressings of their own output, Blackwell says the decision to open the plant is a selfless act. He argues that more overall record-pressing capacity eases the pressure on plants like United Record Pressing in Nashville, which continues to press Third Man releases, and Archer—both of which are backed up and reportedly turning away customers. Also, while no plans are currently in place, Third Man hope to press more than just their own records on-site. Potentially, the plant could offer a new option for young artists and DIY labels. “Part of the concern in this world is that vinyl can very easily turn into an exclusionary thing,” Blackwell says. “But this is going to make it easier for a little punk band to make 300 copies of a 7".”

Blackwell is coy about what else the label has planned for Third Man Detroit, but he makes it clear that the new store will be its own animal. “People shouldn’t expect a photocopy of what we’re doing in Nashville,” he says. “There’s a hope that we do things in Detroit that make us up our game in Nashville.” This is not just hype, bluster, and tourist-trap nonsense, as the bins in the new store will be stocked with records, new and old, by Detroit artists—including two new Third Man signees that have been toiling in the city for quite some time.

Timmy's Organism. Photo by Zak Bratto.

Tim Lampinen, better known by his stage name, Timmy Vulgar, is the best showman of Detroit’s current rock’n’roll underground. He’s wild, passionate, spontaneous, and has a penchant for masks, makeup, and on-stage fireworks. When I meet up with him and his band, Timmy’s Organism, they’re practicing at the Outer Limits Lounge, a bar-in-progress on a quiet corner of the Detroit-adjacent town of Hamtramck, working the kinks out of a track from their new Third Man album, Heartless Heathen. The record is full of Lampinen’s signature mutant-fried guitar and songs about “being tough” and “taking on the world fuckin’ head on,” as drummer Blake Hill puts it. It also has flickers of sobering maturity; “Hey Eddie” is Lampinen’s ode to an old bandmate who died two years ago.

That Third Man even heard Heartless Heathen in the first place was a complete fluke. Before the band went to record, Lampinen thought he was emailing demos to Hill—but when he typed “Blake,” his email’s autofill instead sent the files to his old friend, Blackwell, who had released some of Lampinen’s previous bands, including Human Eye and Clone Defects, on other labels. And when Lampinen was awarded the highly competitive Detroit arts Kresge Grant in 2010, it was Blackwell who wrote the letter of recommendation.

Lampinen also has history with White, who produced the first Clone Defects single (credited as The Third Man) and brought the band along on a White Stripes tour in 2000. But as the Stripes, the Hives, and the Strokes blew up, Clone Defects lingered in obscurity. “We were like, ‘Why can’t we be as popular as the Hives?’” remembers Lampinen. “And then we were like, ‘Oh wait, we’re crazy and we all drink way too much and we follow the White Stripes in a little minivan and put our equipment underneath their bus.’”

Fifteen years later, Timmy’s Organism’s contract with Third Man offers Lampinen the most significant support he’s ever received. Though they haven’t changed their sound or become more commercial, they can now stay out on the road for longer, pocket a little more money, and, with Third Man’s co-sign, there’s a chance they’ll reach a wider audience. In every respect, Timmy’s Organism stand to gain more from this relationship than Third Man.

“I’ve seen a lot of Detroit bands that don’t go on the road as much or get the recognition they deserve,” says Lampinen. In March, the frontman was hanging out with another local band, Wolf Eyes, talking about his deal with Third Man. The veteran noise-rock act told him they were having trouble finding a label for their new album. Lampinen texted Blackwell on the spot.

Wolf Eyes. Photo by Doug Coombe.

Wolf Eyes’ Nate Young and Jim Baljo are discussing circumcision in the backseat of my car while guiding me through their hometown. “They hacked me,” Baljo reveals mournfully. “Turn right at the next light to get on the expressway.” When we arrive at a venue and cafe in the Eastern Market district called Trinosophes__,__ they’re right at home: Baljo washes dishes there sometimes, and they’re chummy with at least a dozen passersby. They post up in the alley out back with coffee, cigarettes, and a spliff.

“I have my pop-out quote ready,” blurts out Young. “‘After playing the largest public Satanic event in history, it made sense as to why we signed to Third Man.’” This is what it’s like talking to Wolf Eyes on this particular day—completely absurd. Young started Wolf Eyes as a solo project in 1996, and while they’ve changed lineups several times in the past two decades, they’ve made an enormous pile of music. They’re always recording, always hustling, and always maintaining a healthy sense of humor.

When the announcement went out about their new Third Man album I Am a Problem: Mind in Pieces, the mismatch was evident—White, whose Lazaretto was one of 2014’s biggest vinyl sellers, had signed a bunch of DIY diehards with a proudly limited appeal along with a massive discography filled with limited-edition Trip Metal experiments. But even as they acknowledge the odd pairing, the band say it was a logical decision.

“We had a couple record labels blow smoke up our ass and we were a little disenchanted with the whole vibe,” says Baljo of shopping around the new album. “They didn’t seem that excited,” adds Young. But Blackwell’s response encouraged them. “We sent him one five-minute song and he wrote back while he was listening to it,” says Young. “That’s fucking great.”

White also sent Young an excited email shortly after they struck the deal—and it wasn’t Wolf Eyes’ first brush with him. Local legend has it that Wolf Eyes and the White Stripes once shared a practice space, and, one day before a gig, band member John Olson grabbed a little combo amp that was lying around. By the end of the show, the amp was in pieces. It was White’s amp. “[Olson] was freaking out,” remembers Young.

As the story goes, Olson replaced the busted 12-inch speaker with a much smaller one, handed it off to White without explaining what had happened, and the White Stripes headed out on tour. “We like to joke about it now, like that’s why we’re doing the record with Third Man,” says Young. “Like, ‘Jack has to pay us back for that tone, man.’”

That hypothetical payback came around in a strange way when Third Man recently bailed Baljo out of jail after he racked up 32 tickets for driving violations. “In Detroit, it’s cheaper to get a ticket than it is to get insurance, so I did this experiment,” he explains. “It got really out of control.” On his way back to the U.S. from Canada, border patrol threw him in jail for four days.

The band explained the situation to Blackwell. “Ben understands,” says Young. Recounting the story, both Young and Baljo are still in disbelief. “That never happens,” says Baljo, adding, “I mean, for rappers, maybe.” Young concurs. “We’re fucking rinky-dink,” he says. “We’re not a big name and it’s not a huge investment to protect us. It was just a nice, classy thing to do.”

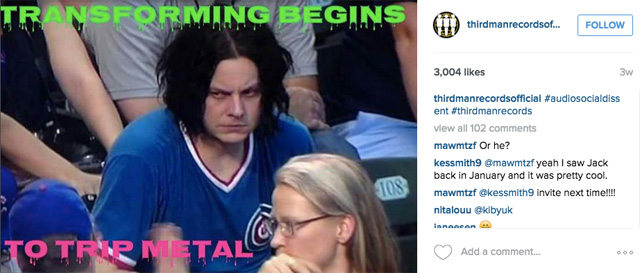

To return the favor, Wolf Eyes took over Third Man’s Instagram account for a weekend, terrorizing the label’s fans by sharing multiple images of a scowling White—including one where his head is lodged in the gap between Baljo’s front teeth. Blackwell says everyone at Third Man loved it.

A taste of Wolf Eyes' recent takeover of Third Man's Instagram account

If White, Blackwell, and Swank wanted to offer a love letter to their hometown with their latest initiatives, they’ve covered a lot of ground. And there’s more to come, as Blackwell has expressed interest in working with even more regional artists moving forward. “I feel so enamored with the entirety of Detroit musical history,” he says. “Anyone adding to it or being a part of it—that’s important to me.” And remember: That includes the Insane Clown Posse, who released a Third Man single in 2011. (Apparently, the label has been trying to lock down a collaboration with Bob Seger for years, too.)

Third Man’s desire to give back to Detroit is undeniable, but how do Detroiters feel about their return? Aside from some skepticism about White co-owning the building with Shinola founder Tom Kartsotis, the reactions from the locals I talked to were overwhelmingly positive. Granted, such praise comes with the caveat that any negativity could get back to White—and to his hypothetical shit list—but doesn’t discount people’s genuine enthusiasm.

“If they bring any of the things that the Nashville store does here, how can you not be excited about that?” says Mike McGonigal, former Pitchfork contributor and current Music Editor of the Detroit Metro Times. Greg Baise, Curator of Public Programs at MOCAD, echoes this sentiment. “[Ben Swank] and I were talking about some of the film programs they’re doing in Nashville, and if that model translates to Detroit, then of course I'm really looking forward to seeing what they do.”

Dion Fischer, former member of early White Stripes contemporaries the Go and co-owner of the venue UFO Factory, thinks that it’s only a good thing to have a cool new spot in circulation, somewhere to hang out before a show and after dinner. He also agrees that the label’s investment in Detroit bands and “crazy ideas” are good for music discovery on a larger scale. “If you like the Timmy’s Organism record and find out they were influenced by the New York Dolls and Hawkwind, you’re going to go check out those bands,” he says.

Protomartyr, one of the best Detroit bands to have cropped up in the years following White’s departure, set many of their bleak, violent, and wryly funny songs within their hometown’s unique milieu. Does frontman Joe Casey think he’ll be shopping at the Third Man store with any regularity? “No, I don't,” he says, “But if you've got a tourist in town and you want to show them around, that’s a place they can go.”

The label has hired a handful of people so far to help run Third Man Detroit, including at least one name of significance: Dave Buick, who ran the Detroit label Italy Records, released the earliest White Stripes material, and gave Blackwell his start in the music business. With Buick on board, not only is the new store a manufacturing enterprise and a commitment to Detroit’s history—it’s a family affair.

“To have the guy that put out the first two White Stripes singles working in that building—and have those White Stripes singles for sale in there—there’s a beauty to that,” says Blackwell. “And having that happen two blocks from the Gold Dollar, where the deals for those singles were hashed out and those songs were played for the first time, it just feels really, really good.”