by By Mark Richardson

November 13, 2013 Photo by: Hanly Banks

"As a kid, I was just a kid. Average."

This is the voice of Bill Callahan. In person, it’s higher than it is on record, somewhere between the chesty baritone of his recent work and the reedy plea of his youth. In September, I met with the 47-year-old singer-songwriter in the living room of an apartment on the Lower East Side of Manhattan and talked to him about his childhood: He grew up in Maryland and England, his parents both worked for the National Security Agency, he lived in the suburbs. "High school was terrible for me, like it is for all people, I guess. I was just not happy," he tells me. But then something about the sentence that followed stuck out. As a kid, I was just a kid. It sounds like a line from a Bill Callahan song. Is he saying "Let’s leave that alone," because there is something deeper he doesn’t want to discuss, or is it that there is really nothing there? Does it matter?

People who conduct and read interviews with Bill Callahan know that they can be challenging. He's been known to comport himself as if he doesn’t want to be there, and he doesn’t necessarily have much to say. Sometimes it’s comical. His perceived reticence can mirror his work as a whole: As a writer, Callahan is a minimalist. He strips down verbiage until mostly silence remains, and when you’re doing interviews, silence is your enemy. “Some people write a thank you note for a gift and it’s three pages long, and some people write a thank you note and it’s five sentences—that's me," he says. "I like to pare away words because I don’t want to waste anyone’s time.” Minimalist writing pairs with minimalist talking which leads to a minimalist Q&A, which can be the worst kind.

On this day, though, Callahan is friendly and seems happy to talk. But I wouldn’t describe him as open, exactly. He answers the door in a red plaid shirt and jeans. We exchange pleasantries as he heads to the kitchen to work a French press, and then his publicist buzzes up from the street, enters, and asks if he needs anything. The publicist suggests a smoothie for later, and Callahan agrees, asking for something with greens. The building is a classic New York tenement, but the apartment itself, which belongs to a friend, is tidy and well kept. There are a few CDs in a rack on the wall, some art books piled up here and there, an old air conditioner humming away in a window framed by green curtains.

As Callahan answers questions slowly and carefully, I think about how his public persona connects to his work. Bill Callahan the person has always been glimpsed through a veil. Early on, when he was making noisy lo-fi blasts as Smog, it was the pseudo-anonymity that came with working under another name and under the radar. If no one knew much about him in those years, it’s because, relatively speaking, virtually no one had heard the music. Little by little, as he achieved a certain amount of indie-level fame, the man began to show himself, but only so much information ever entered the frame.

You got the sense that the ratio between what was revealed and what was held back was quite small. This brings up questions about the relationship between the maker and the made, how the knowledge of the songwriter changes how the songs are heard, how songs can be an interface with the artist, and how the work can stand alone. As Callahan pauses to take a sip of coffee, I think about sharing, about wanting to be known. We put pieces of ourselves out in the world in part because we’re lonely. We want to be asked about our lives, we want people to care. And when they show no signs of doing so, we tell them what we’re about anyway. But Callahan seems to inhabit another space. He wants to make music and he wants to play it for people, but he doesn’t seem to care if strangers get to know the "real" him.

We talk about the internet. "It’s irresistible. It’s a drug almost," he says. "I try to use it constructively." But he doesn’t like reading about himself. "I was late to the internet. I didn’t really understand what it was. I didn’t know what an email was. Then I was like, 'Whoa, let me see if I’m on this thing.' I read stuff [about myself]. It was a terrible, terrible experience. Positive or negative, it still feels awful. I just told myself that I was going to stop. I didn’t think that I'd able to, but I did. Every day I don’t Google my name there’s another beautiful day."

Callahan’s power as a songwriter comes from observation. He finds things that don’t initially seem notable and then puts them under a microscope until we see something new. By imbuing simple objects with symbolic power and laying them out clearly, he can create an image or a feeling that seems closer to the person hearing it. One of my favorite Callahan songs, "Driving", from the 2003 album Supper, is one that bridges the crude, one-line goofs of the early days with the more arranged and better produced music of his later years. Its only line is: "And the rain washes the price off of our windshield."

Callahan layers his voice so that the refrain sounds like a shackled crew of ghosts moaning from the afterworld, and he sings those words incredibly slowly, letting each syllable tell a story, surrounding the image with guitar and banjo and brushed drums and sound effects including exploding bottle rockets. But that one line is the thing. And when you hear Callahan sing it, you can see that car with the soaped-on price pulling out of the lot, and the water dissolving the numbers, drop-by-drop. From the tone, you gather that the price is not terribly high, and the driver is not terribly excited about the world seeing what he can afford when it comes to buying a pre-owned vehicle. That's a lot for one line. But then again, that’s me filling in the blanks.

"I still feel very hopeful after

I finish a song, like I’m going

to save the world—that feeling

dissipates as soon as people

hear it and that doesn’t happen."

—Bill Callahan

Callahan’s work to date exists in three stages. There is the noisy experimental period—which contains his darkest, most gothic (and funniest) work—from 1990’s Sewn to the Sky through 1996’s The Doctor Came at Dawn. (The pre-Sewn period, when Callahan published a zine and put out his earliest tapes, is a past he doesn’t care to mention.) There was little on these records that could be described as songs; there were experimental collages, mixing guitar feedback, voices, found sounds, loops. “It was like a monkey throwing its shit on the walls," he says of that time now. "It was a tactile period, so I was really into the textures of sounds and the way the microphone would distort something. That fascinated me."

But behind the static and the name was an aesthetic sensibility. There was humor, found in titles like "Bad Ideas for Country Songs" and "High School Freak". But it was almost impossible to imagine the person behind it all, and Forgotten Foundation's cover painting and buried voice offered few clues. By 1993’s Julius Caesar, Callahan was edging toward something that could be called a Songwriter. It's a lo-fi album with delusions of grandeur; there are string sections and a loop of a Rolling Stones song, and all that was further refined on 1995’s Wild Love, which contains "Bathysphere", one of his most enduring songs. "I think the heart is still the same," he says of this early material. "I still feel very hopeful after I finish a song, like I'm going to save the world or something—that feeling dissipates as soon as people hear it and that doesn’t happen."

The second phase of his career starts with 1997’s Red Apple Falls, the first of his albums I heard and the first of two Smog records he recorded with Jim O’Rourke. There is no comparison as far as sound quality between the O’Rourke pair and the formative releases. The producer favored dry, simple recordings that captured the sounds of instruments in a room, and this stripped-down approach gave Callahan’s music new possibilities in terms of space. It’s an approach to recording that has continued, and to my ear O’Rourke helped clarify the mode in which Callahan sounds best on record. Callahan doesn’t quite agree with this assessment, but he does credit O’Rourke’s enthusiasm. "He was the first engineer that gave a shit about my music," he says. "I started out recording at home by myself and then I was randomly going to studios with people I knew nothing about. So having someone sitting behind the glass actually saying 'Wow, that was good!' Instead of just, 'What’s next?' was a big thing."

Beginning with the more memorable and constructed songs on Wild Love, continuing through The Doctor Came at Dawn, and fully realized on Red Apple Falls, we finally got a sense of some of Callahan’s primary concerns as a songwriter: This was bleak music, often darkly funny, about love, sex, and alienation. "All Your Women Things" finds a man contemplating the items left behind by a departed lover and creepily making a "spread-eagle dolly out of your frilly things." On Red Apple Falls, "Ex-Con" begins with a wink—"Whenever I get dressed up/ I feel like an ex-con trying to make good"—and ends with a couplet that made some sense in 1997 but makes 10 times more now, when so much of life is lived behind computers: "When I’m alone in my room I feel like such a part of the community/ But out in the street, I feel like a robot by the river."

People used to wonder if Callahan’s knowledge about how lovers torture each other came first-hand (speculation fueled, in part, because he had girlfriends with their own amount of fame in the independent music world—the late Cynthia Dall, Chan Marshall of Cat Power, and Joanna Newsom). We’ve all heard from songwriters who go out of their way to tell us they are not writing autobiography, but even the most elusive of these have some desire to be known. You don’t stand in front of hundreds or thousands of people to perform unless you like to be looked at and listened to.

Callahan’s relative blankness and elusiveness serve him well, keeping our knowledge of him as a person apart from the work. But it's easy to forget that he’s not exceptionally private. There are singer-songwriters who reveal much less. He’s taken many photographs. He participated in Apocalypse: A Bill Callahan Tour Film, and there has been a book of photographs documenting his life in Austin called The Life and Times of William Callahan. He does interviews to help the word get out because he knows that’s how the game works and he’s been playing it for a very long time, but he seems to believe, somewhere deep down, that his personality and the details of his life are inessential to the enjoyment of music.

"I love life more than I ever have,

and I've stopped caring about

things that don't matter. I think

we were designed to die happy."

—Bill Callahan

After Red Apple Falls and 1999's Knock Knock, Smog was well established as a project, and Callahan stayed busy in the first half of the last decade, releasing three albums in three years. But by the time of 2005’s A River Ain’t Too Much to Love, his masterpiece, some things had changed. Making music under the banner of a band name began to seem less appealing. "The word 'Smog' meant nothing to me—just like symbols on a slot machine, like a cherry or a horseshoe. I realized that’s what I was broadcasting, that’s the face I was giving to people." Starting with 2007's Woke on a Whaleheart, he began releasing music under his own name. And though he sees all of his work as existing on a continuum, he acknowledges that more people started to take notice. Which doesn’t mean that the music was any more or less "him" than what came before.

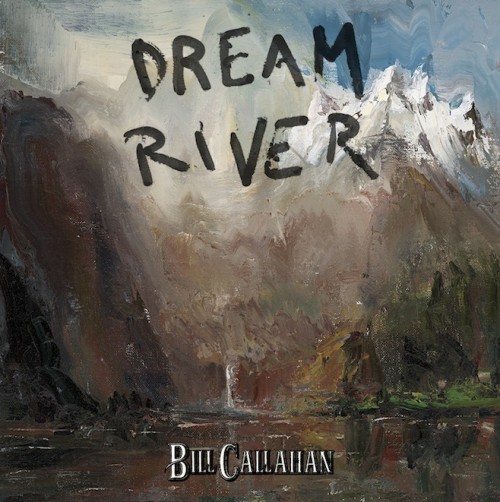

As a performer, and in terms of record sales, Callahan has experienced more popularity in the last few years than during any other time in his life. And if you follow the press around an album cycle, you can see the same questions being asked, and the answers give little nudges to a song’s meaning. His new record Dream River, for example, can be understood as a concept album, as a narrator slips into a dream at the start and returns to reality at the end. Callahan accepts the role of the unconscious as a source for creativity, and he trusts it to take him to places that are meaningful.

"A lot of it is subconscious coincidence," he says. "I think about certain themes in my life and focus on them. That’s what makes a record hold together, because there might be some aspect of a sound or of human nature that I’m thinking about a lot." He trusts in his ability as an editor to take the raw material that bubbles up and shape it into something that feels true to his idea and is also coherent to his audience. He can tell just from singing something when it doesn’t ring true, and the discomfort that settles in when he sings such words gives him a palpable feeling of nausea. For Dream River, he says, "The theme was love, which is not the most original topic for a song, but it’s the only thing that matters."

This is a shift. For much of his career, the primary preoccupation of Callahan’s work was death. See "Permanent Smile" from 2000’s Dongs of Sevotion. There, death was something earned, a fate that led to the smile of the skull as a twisted, eternal state of bliss. Now, he’s a little self-conscious about how much of his work focused on it. "[Death] is something that I try to avoid in songs and in life, but it’s hard," he says. "It’s just the big joke at the end of existence. I feel like I’ve covered that enough."

Callahan is engaged to marry Hanly Banks, the director of his tour film and the photographer behind his new round of beatific press photos. Things are great for him. “I love life more than I ever have, and I’m comfortable," he says. "I’ve stopped caring about things that don’t matter. I think we were designed to die happy." But Dream River is far from a "happy" album. True, there is "Small Plane", a beautiful ode to simple togetherness and easy bliss that only hints at dissolution ("I always went wrong in the same place, where the river splits to the sea/ That couldn’t possibly be you and me").

"I do think it’s kind of the essence of the record," he says of the track. "I dreamed the images and then woke up and wrote it down in five minutes." But much of Dream River is about loneliness. The songs are sparsely populated, with almost no one in them. One character drinks alone, another spends a long summer painting boats in a marina. Unlike Callahan himself at this moment, it’s never comfortable.

We’re wrapping up in that Lower East Side living room, and I ask Callahan about "Teenage Spaceship", one of my favorite songs of his, and one of my favorite songs period. His answer is long, drawn from a distant memory that is still vivid. And if you know this song, and you imagine what it might mean, you can see in his answer how the process could work, how the most routine moments can be held up to the light and transformed. It's one of the quietest and most subtle songs in his catalog, consisting mostly of three slowly plucked guitar notes and wisps of drone, and it tells a story from the perspective of a young spacecraft flying around a neighborhood at night. "People thought my windows were stars," goes the refrain.

"I was living with my parents in their basement in Maryland and I used to have bad sleeping habits, and I wouldn’t really get going until midnight. That was when I started my day. So I’d go for a walk around midnight every night. I’d go for an hour, hour and a half, and I probably saw another person only once. Everyone’s in bed, everyone’s in their house. It’s just you and the stars and moon and an abandoned sleeping town. But I was very awake, contrary to everything else that I could see around me. So I was very much like an alien being—that’s probably where there spaceship thing came from— walking through a strange land that was going through something very different. They’re all sleeping, and I’m awake."

A walk at night. It’s the kind of ritual we’ve all engaged in, nothing to it, the fact that it was his life is incidental because we’ve all been there. But Callahan found a way to get to its core and extract some kind of existential meaning from it. As a kid, I was just a kid.