The writer of Heaven Will Be Mine on how she made 2018's most interesting game

Big robots, big moods

If it was socially acceptable to ask people who made cool things to explain them to me, I would absolutely do this for everything, all the time. “Bloody hell, that cake was delicious. Please describe to me the process of making it, how much planning you had to do, and what the ingredients mean to you. And also what you think of current cake culture.”

I was very excited to talk to Aevee Bee of Worst Girls Games, because she wrote Heaven Will Be Mine. Made by Worst Girls and Pillow Fight Games, it’s a visual novel that Bee described as "a season of a giant robot anime if all the mecha pilots were girls and all the gay subtext was was actually just happening instead." It was one of the most exciting and interesting games I played last year. It’s also the sort of game that I can’t imagine how to make. So let’s start at the start.

We sat at an empty table to talk, and as we did Bee's hands were almost never still. She drew on the white tablecloth with her fingers, and smoothed it over again with flat palms, like sand drawings or an etch-a-sketch only she could see. But at the same time she was speaking endlessly, spilling out ideas quickly and clearly, almost without pause for breath.

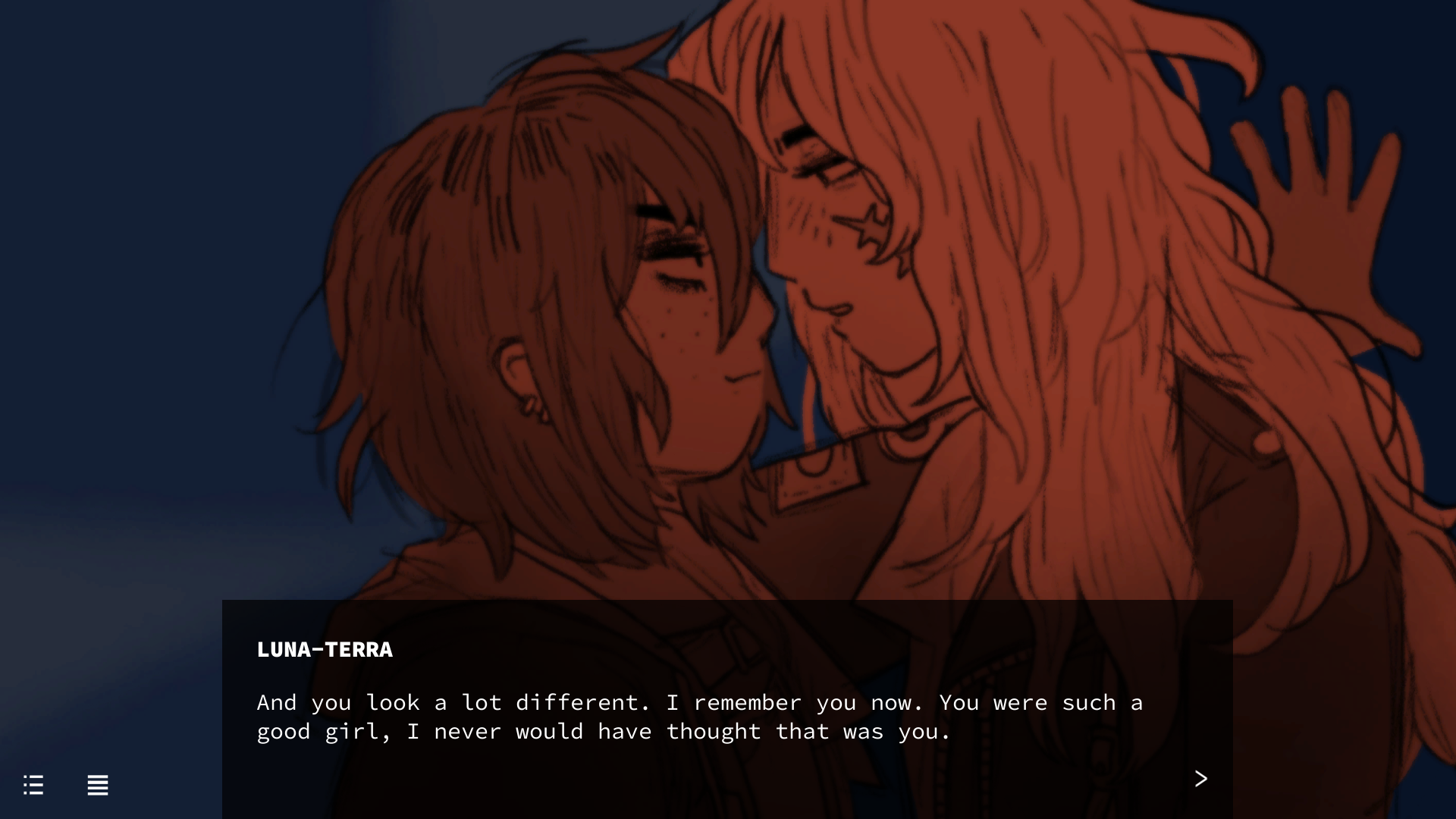

The initial inspiration for Heaven Will Be Mine, she told me, came from anime fandom and art scenes, especially yaoi and slash fiction, where women (often queer women) create gay male romances. Bee said she doesn’t think the genre necessarily has much to do with gender, and is more a workaround to explore emotions and feelings in relationships where both partners have equal agency. At the same time, she said, they wanted to portray lesbian relationships that weren’t safe, reserved or desexualised. “A lot of times there can be really good reasons for that,” she said, “but for some other people it's not very reflective of their experiences. Even if you're a woman who loves other women, you're sometimes in really fraught relationships.” Bee said she knows a lot of lesbians who are into yaoi because of what it provides emotionally that they can’t find elsewhere.

This lead to looking at the male rivalries in the big-robots-smashing-each-other stories in anime and manga, like Char and Amuro in the original Gundam. These matchups are often seen as sexually charged in their intensity. “We were like ‘... What if they was girls, though?’” she said.

The three main characters in HWBM, Luna-Terra, Saturn and Pluto, all pilot variously huge robots, although they don’t look like the blocky 80s transformers you might imagine. In some early versions they planned to not depict said metal monsters, called ‘ship-selves’ in the game, at all, as lead artist Mia Schwartz (the other half of Worst Girls Games) wasn’t confident in her ability to draw giant robots. This seems reasonable as a general concern. I’m glad they do appear, though, because in their final form they’re beautiful, imposing works of art. I hear crystalline tinkling in the back of my head when I look at one, the screaming of a cat at another. “I love her designs, I think they're really really good,” said Bee. “I wanted them to feel really soft and plastic and expressive and abstract.”

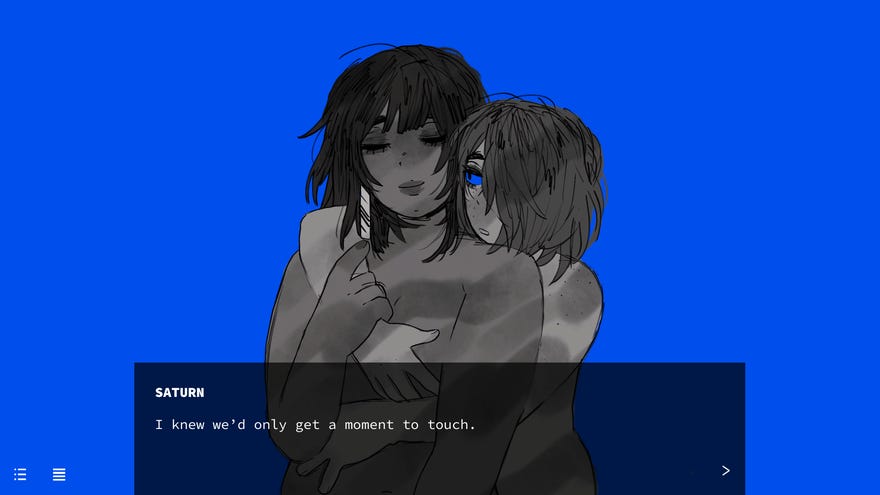

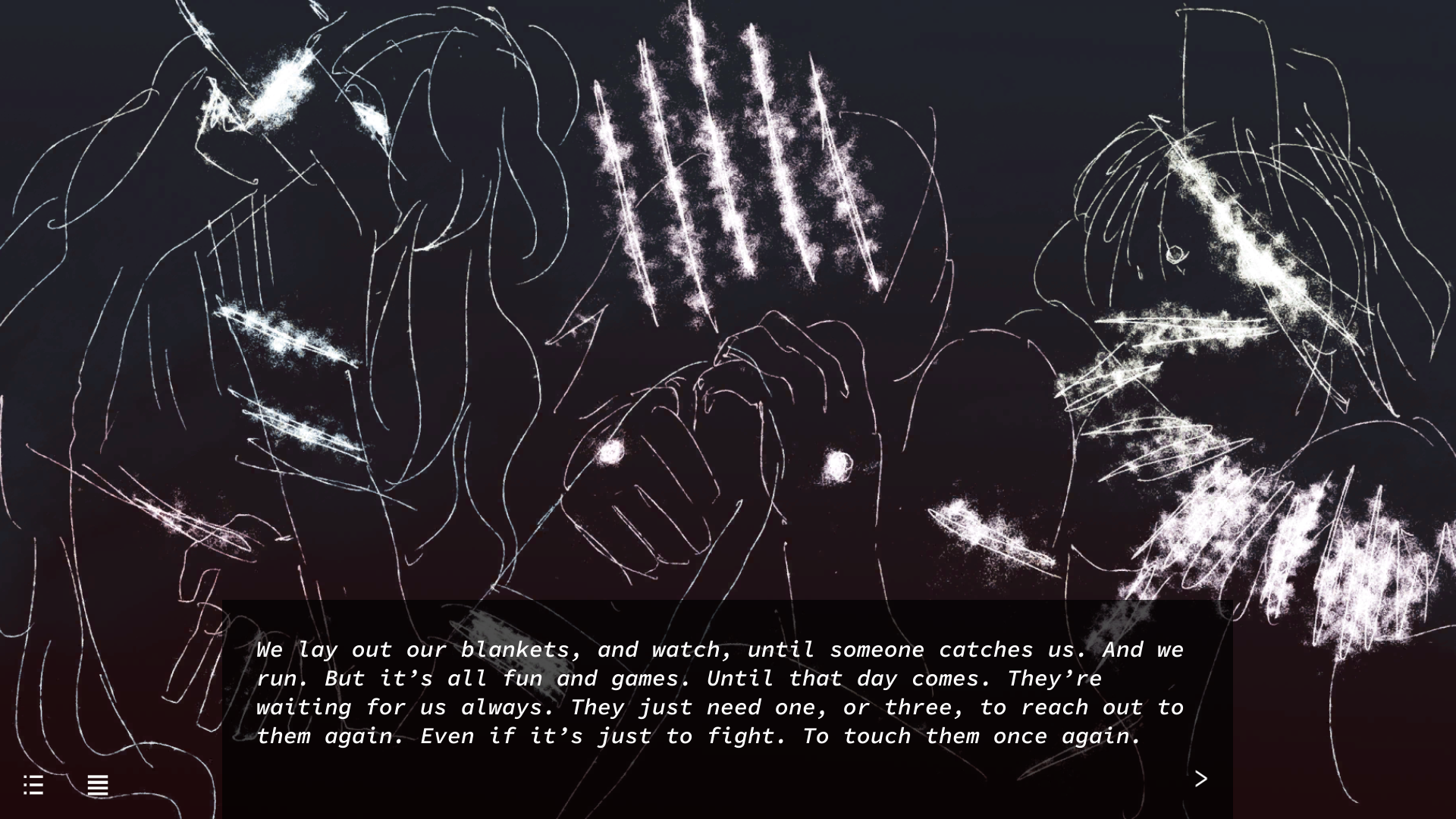

The abstract is key, because of how the ship selves interact. The three pilots are all on different sides of a fight, and when they face off against one another the results feel both alien and intimate, thanks to both the strange but recognisable forms in the art, and Bee’s descriptions. Her writing in these sections has an alarming clarity for something almost impossible to imagine experiencing.

Bee explained this by describing how shows about giant robots are primarily shows about people having emotions at each other. There’s no practical reason, she said, to have a giant robot in general, nothing that would make it more efficient in any conceivable way. She cited an episode of Austin Walkers’ Friends At The Table, where he says “We could have made them look like anything, but we made them look like us.”

In HWBM, they have giant robots because they’re deliberately trying to change war into what it’s like in anime, where "every laserbeam you fire, every attack you make is an expression of your feelings.” The characters are able to have an intimate, fighting-as-flirting interaction in a very safe environment, because they’re protected by giant metal bodies. They are not, Bee said, ever going to get really hurt, or affected in ways they don’t want to be.

After the core concept came pre-production, “so that the scope didn’t blossom out of control.” Bee described herself as very production focused these days. “I went from 'I'm really focused on writing and design' to 'Oh, I actually have to be focused on production, and thinking about all of these things, and really taking this into consideration with how I manage the team'.” For both HWBM and their previous game, We Know The Devil, Bee and Schwartz locked in what the key choice of the game is based around, and how information is presented to the player, before anything else.

“Thinking about the UI came with the beginning of the design document,” Bee said. “Even before I was like ‘what are the endings'. The endings usually come last for me.” In HWBM they decided on a diegetic computer UI, as if the player was in the cockpit of the giant robot, embodying the character they’d chosen. This allowed them to use different storytelling techniques, things like chat conversations and emails, that filled in the world and made the universe around the game feel real and lived in.

Bee uses Scrivener, a piece of outlining software designed for writers, which allows her to block out all the pieces of text needed for a project. “Every day, we'll have one chat," she explained, chopping up the different pieces on the table. "A mission will be this long, it will have a choice point or not have a choice point, etc.” From there the first draft was just a matter of filling in all the empty blocks, which also let them identify other needs. They were able to decide, for example, roughly how many art assets Schwartz needed to create: there’s going to be a picture of this fight, there’s going to be another thing here, and so on.

The key choices, meanwhile, relate to three different factions, in a sort of parallel universe version of the 80s, who have different goals for the future of humanity. Each pilot represents one of them. The Cold War happened, but was in space, and against an external something known as The Existential Threat. In this way, Bee said, HWBM is like a sequel to a game that never happened, because the war, character histories, and other significant events are alluded to but not always made explicit. Crucially, in this universe, culture has a literal weight. Gravity is a physical and metaphysical force that humans generate, giving them power over the universe and each other. The characters want to change the culture, but how can you do that without changing yourself? The central tension comes from a kind of metaphysical risk of becoming so detached from humanity that you’re unable to communicate with or understand them -- that you become literally and figuratively alien.

It’s a wider metaphor for the experience of being an othered person in mainstream culture. Part of Bee’s research involved looking at the space program in the 60s and 70s, and linked to that she saw themes of idealistic, enlightened futures that were a part of American education and public services like PBS. “These kids who were raised with these really idealistic values then become unable to connect with the culture,” said Bee. “That culture won't actually accept them because they can't quite rid themselves of their preconceptions and hangups about who qualifies as human or not.”

The factions developed out of that tension. The Memorial Foundation wants them all to return to earth, as the longing and obligation for humanity to be together overpowers everything else. Celestial Mechanics wants to abandon humanity completely. The third, Cradles Graces, opts for a kind of reconciliation between the two. Bee said that in some ways the latter was the hardest as it meant she had to put extra work into making the other two more sympathetic. “It's kind of like, ‘Oh that feels like the right answer’, and I didn't necessarily want it to feel like it's the totally correct answer.”

Two of the women are explicitly trans women, but they’re all othered not because of that, but because of the cultural and physical changes they underwent as space pilots flying giant robots. The characters in HWBM are all established adults partly as a counterpoint to the teens in We Know The Devil. Bee wanted to show a variety of ways of living and being. That they’re trans is “present and unambiguous, but also not the central focus of the narrative.”

All three grew up in a now “semi-failed” Utopian society, where, Bee explained “they were allowed to perfectly be themselves, until they weren’t.” They encompass different life experiences within that -- Luna-Terra is slightly older, and didn’t have the same nurturing childhood as Pluto, and Saturn has fraught experiences in her past as a pilot. Their different personalities act as foils for each other. (The original trio was going to feature a character called Mars as a youthful foil to Luna-Terra, but they realised she functioned very similarly to Saturn. Mars became a secondary character working with Pluto.)

“I thought it would be crucial to have more ways of being, and for it to be, not like transness as metaphor, which I think is really cheap, but I think to talk about their othering in this really fundamental way that's about their disconnection.” Bee compared it to her own friend groups, an “assortment of all kinds of different queers from a lot of different walks of life” who have different histories and pasts, but still find community with each other through their shared experience. “Not every part of your history comes up in every conversation. But a lot of what's fundamental does,” she said. “It's not like saying 'We're over being queer, we've come out and now we don't talk about it any more', but it’s something that's so suffused through their lives that it doesn't necessarily need a specific reference.”

This links to the game existing at all. I asked Bee for her thoughts on visual novels as a genre, referencing Aimee Hart's argument that it's a haven for queer stories. For a start, she said that she thinks there’s nothing that happens in narrative design in all other games that doesn’t happen in a small way in VNs, citing all the different types of conversations and UIs that are present in HWBM. But Bee also said that we talk a lot about visual novels as a low cost way of making a game, but forget that it’s also a low cost way of making a novel -- easier than going through a big publisher, or trying to self publish somewhere like Amazon. And that makes it easier to reach an audience.

“I make games for anyone who wants to read them, and anyone can. I don't think anyone is exclusive about the audience that it's for,” she said. “But I am thinking of my community and the people who are young queers, and older queers, and people my age, when I'm writing those stories. So I want it to be accessible to that audience.”

In the end, the three protagonists of Heaven Will Be Mine always end up together. It’s not meant to be the payoff to a big revelatory moment, but rather the continuation of a relationship, working on it, growing it. “None of the futures that they end up with are really that great. They're all flawed in their own way,” said Bee. “I have this idea of moving our games from ‘here's the idealist thing’, to ‘here's some flawed stuff’, and ‘here's us trying to figure out ways to be happy even if we have a bad future.’”

I couldn’t pin Bee down to her favourite ending, but she did cop to the Memorial Foundation ending being significant to her, the one where all three end up living a relatively normal terrestrial life together. The other endings, which involve metaphysical ascension, cool revolutionary separations from earth, had to be made flawed. The Memorial Foundation one was almost the opposite. “I don't mind if it's nobody's favourite, actually, even not really mine, as long as people appreciate what it's trying to say. That basking in each other's simple mundane presence in itself can be enough.”

My favourite ending, I told Bee, is the Celestial Mechanics one. In that, the three women enter a gravity well and give up humanity entirely. They become something entirely different; to an unknown observer the three take up the entire sky together as sparkling nebula, literal star stuff. The combination of Schwartz’s art, the heart-swelling synth soundtrack from Alec Lambert, and more of Bee’s intimate abstract text make for a real out-of-body epic sci-fi experience. I understood that not all things are for me, that I cannot know every experience, but nor should I -- and, importantly, it does not preclude me from seeing that those experiences are still beautiful. And it is why I liked HWBM so much. It is not mine, after all -- it is theirs!

Now the game is out, Bee said she's sort of in rest mode, though there are plans for things like an art book zine, and Schwartz is working on ideas for merchandise. Bee is thinking about the next game she produces, which she anticipates won’t be a visual novel. They’re looking into possible sources for funding. The team didn’t have a lot of income when making HWBM, and Bee has a full time job separate from her game dev work. She is interested in the complicated questions about how one can fit development into life in a way that is sustainable, but she doesn’t have the best answers yet. But the themes of the game she makes, I think, are likely to stay in the same ballpark.

“I want to make more and more games that are about adulthood and later adulthood, and that explore what it's like to be an adult queer person. The idea of there being a future. Which I think is a really hard thing, sometimes, for us to hold on to.”

An earlier version of this article stated that all three characters are trans women. In fact the game deliberately refrains from confirming whether Saturn is cis or trans.