The story of Unreal Tournament, the ambitious project left drifting in space

Fire retro rockets

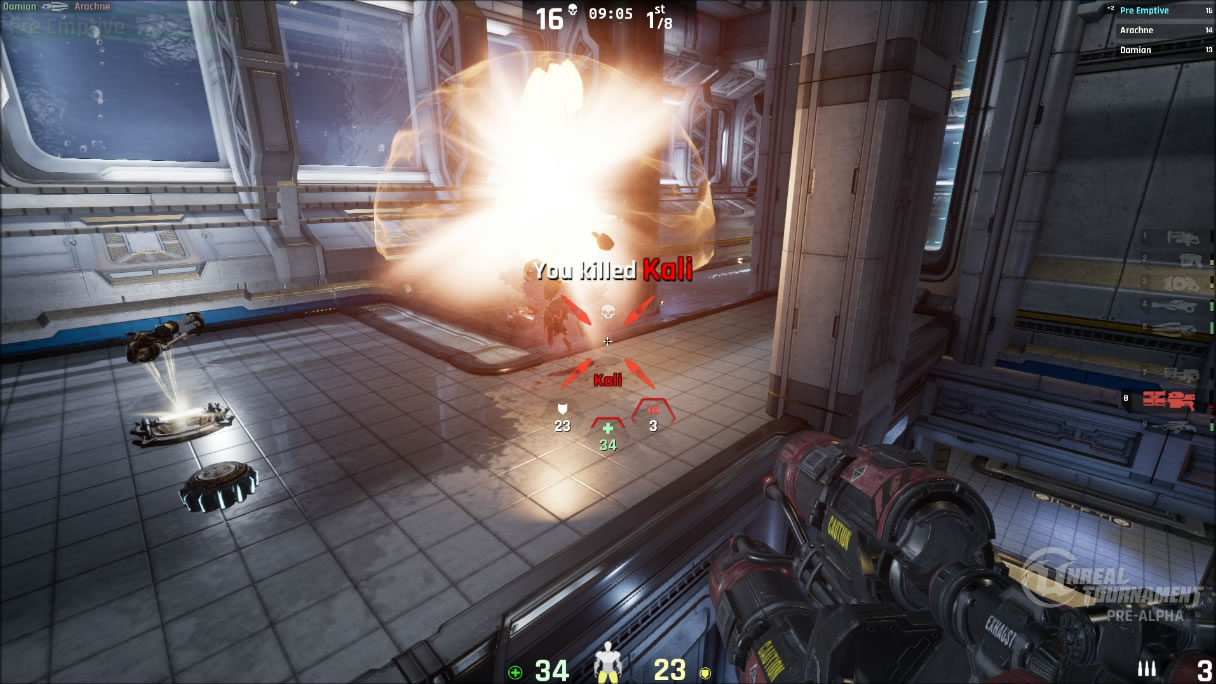

Scroll right down to the bottom of the Epic Games Store, and you’ll find a forgotten and totally free, game. It’s existed since before Epic set about its masterplan to take over the PC games market, but now, buried beneath the exclusives and novelties, lies Unreal Tournament, the latest entry in the iconic shooter series, whose development was halted in 2018.

The game disappeared quietly, and I wanted to peek behind the curtain. To try and find out what happened, I spoke to some of the leading community contributors, as well as a contracted developer who worked on the project. The story that emerged suggests the community and the developers were never quite sure how to coexist, or how to turn the dream of open development into a reality.

The open development was supposed to make Unreal Tournament a unique project. Announced in May 2014, it would be headed by a small team of fewer than 20 Epic developers, and share all game code, assets, and design decisions throughout development with the player community, allowing the fans to take part in a more direct way. It was exciting but vague, with even the announcement on Twitch warning that “we don’t have everything figured out yet”.

The early details didn’t reveal much more than that, but at a time when Kickstarter and Early Access were just starting to prove themselves as viable community-inclusive models for game development, the idea wasn’t too outlandish. Unreal Tournament would be completely free, propped up by a marketplace where creators could monetise their work while giving Epic a cut.

The project began with plenty of momentum. Forums and Discord channels were set up shortly after the game was announced, community streams were rolled out every week, and key figures in the UT community -- pro players, developers, fansite owners -- would occasionally visit Epic’s offices to discuss development.

“Wailing” was a community developer who went on some of these trips, and got to talk about the game with key developers like project lead Steve Polge. Wailing says that Epic’s initial announcement had huge promise. “There was no Overwatch, no Quake Champions, and the entire Battle Royale genre was essentially limited to DayZ and other low-budget knockoffs. In a rising tide all ships rise, and there was a lot of excitement to make this the ultimate Unreal Tournament.”

“I found it’s a real slippery slope talking out in public,” says Joe Wilcox, who worked on Unreal Tournament as a contractor. He says that the sheer volume of community input quickly proved challenging for the small internal team. “On the dev team we already had two ‘camps’ with their own desires. But in the community there were tens to hundreds of camps, and a lot of feedback was contradictory.”

But there was some early success. The legendary Flak Cannon, for example, was concepted and meshed by the community, and a new map, DM-Lea, was created by community member Neil “CaptainMigraine” Moore. The fans were intensely proactive, to the point that even the first playable builds of Unreal Tournament weren’t released by Epic, but by “raxxy” and a small group of contributors on the Unreal Forums. One of these contributors was “Sir_Brizz”, owner of the BeyondUnreal fan site.

“Initially, the source code was locked up behind subscribing to Unreal Engine 4, when it was $19 per month,” Sir_Brizz explains. When UE4 went free, not everyone knew how to produce a playable build anyway. “It, again, made the builds more accessible to the community, allowing them to give feedback that came from actually trying the game.”

According to Sir_Brizz and Wailing, Epic weren’t happy with these builds being released, and it forced them to rush out their own public builds. The unfettered enthusiasm of a community seemed to clash with the structured, heads-down approach of a development team. “By the time we got to a position where we had stuff to explain, any conversation was hard to have due to noise,” Wilcox tells me.

Wailing, who contributed code changes to Unreal Tournament, believes that Epic were lacking a key member of staff. “All of the important work for the game depends on programming, but to outsource this fundamental architecture outside of Epic’s office requires a full-time person capable of interacting with engineers, collaborating on code, and merging it into the game.” He says that this role didn’t exist at Epic; multiple one-line code changes that he proposed in late 2014 were not addressed for a year.

Wilcox admits that the dev team struggled to stay on top of code contributions. “It’s true that it wasn’t super easy to get code in front of us,” he tells me. “People could submit pulls which I was way behind on reviewing, or make something cool and post about it. But I don’t remember many super cool programming projects that showed up in the forums with a big ‘Hey, look at me!’”

With developers going quiet on the official channels, toxic elements began to appear. Valuable contributors, like “Tidal Blast”, a modder who created the 3D model for the Enforcer gun, were turning adversarial. “Tidal Blast repeatedly evaded bans and derailed discussion, to the point of pathology,” says community developer “Cafe”. “There were several other people similar to him that were oppressive to the atmosphere.”

Despite growing uncertainty, the community continued pouring its efforts into the game; “N0niz”, maker of the Bombing Run mode, estimates he put 600 hours in, while raxxy invested plenty of time and money into hosting “top-tier servers used worldwide by players and developers for playtesting”, according to Wailing. A few select contributors earned Unreal Dev Grants (estimated to be worth around $1000 each), or even jobs at Epic, but for the majority, who just wanted to see a new Unreal Tournament game, it was looking more like a thankless slog.

Epic’s frugal approach extended to the soundtrack. Michiel van den Bos, composer on the original Unreal Tournament, offered to make the music for the game, but Epic told him it would be crowdsourced and there would be no financial compensation. “They were just sticking to their guidelines so no harm done,” says van den Bos. “In the end, I wound up doing a test song with some new synths and it ended up similar to a UT track from back in the day, so I sent it off no strings attached and it made it into the game”.

Meanwhile, the dev team began rolling out game modes with Duel, Capture The Flag, and the new Blitz mode (the Elimination, Assault, Bunnytrack and Bombing Run modes were all community made). Blitz was designed with eSports in mind; a 5-v-5 flag run in which one team had to either deliver a flag into the enemy base or wipe out their entire team. The rollout caused more fissures. “Most of the vocal community members I’m aware of didn’t have a problem with Blitz,” says Sir_Brizz. “They were frustrated that new game modes were being built and the foundation of the game was poor.”

Wilcox admits there were disagreements with players over the introduction of new game modes, and suggests they stemmed from the open development process, and the community not understanding how much influence they would actually have. “We started tweaking various things for Blitz that had consequences to Capture The Flag, Duel or even Deathmatch”, he says. “In normal development, that’s 100% okay. In open development, it’s total chaos”.

Vocal minorities in the community opposed changes to the more sacrosanct modes. “We played around with half-time in CTF and short-timed powerups in Duel”, says Wilcox. “Both ideas had important potential roles in controlling the ebb and flow of a game and both, from my point of view, were decried without a fair shake”. But despite difficulties integrating the community, Wilcox doesn’t believe this had anything to do with the game’s eventual breakdown. There’s a big purple llama piñata in the room we haven’t mentioned yet.

The unfathomable success of Fortnite after it launched its Battle Royale mode in March 2017 changed the whole company. “Epic paused UT because of a great opportunity,” says Wilcox. “One that took off beyond comprehension.”

Eventually, community members including Cafe and Sir_Brizz were banned from various channels for expressing frustration at the pace of development. In contrast, Wilcox believes that the alpha was progressing at a good pace and could have moved onto the beta given more resources. “The mechanics felt good, the maps felt good. We had just started really looking at progression and monetisation,” he says. “Could it be completed with a small team? No, but that was never the point. We would have had to increase the team size, especially in terms of testing to finish the game.”

But Epic had no intention of pushing the project forward that way. By 2018, this could well be attributed to the success of Fortnite, but it also seemed consistent with Epic’s philosophy from the very beginning to keep Unreal Tournament as a side-project on a minimal budget. By August 2018, Wilcox and other freelancers had stopped working on the alpha. The fact that development had stopped, however, wasn’t made public until Tim Sweeney revealed it in an interview with Variety in December 2018. It was an inelegant yet strangely apt way to mark the end of a project shaped by confusion and poor communication.

“The small team at Epic that worked on the new Unreal Tournament, as well as many other developers across our organization, were passionate about the project. We’re grateful for and impressed by the community and modders and their outstanding contributions,” project lead Steve Polge tells me, in an emailed statement. “Even though we’re no longer actively developing Unreal Tournament, both the current released version and the UT editor are available on the Epic Games store, so that the community can continue to play the game and create new content and mods for it.”

The community developers who continue to work in the Unreal Tournament alpha are gathered in the UT Renaissance Discord channel. Tamzid Farhan Mogno is one of the its founders. “The channel has helped contributors communicate better, help each other & experiment with the current state,” he says. “Those who are not actively developing help others with their knowledge.” UT Renaissance did their own community development stream a few months ago. Wailing and a few other UT exiles, meanwhile, have returned to working on a long-standing open-source slant on Unreal Tournament called Open Tournament.

It’s possible -- probable, even -- that the Fortnite juggernaut would’ve subsumed Unreal Tournament’s development anyway, just like it did Paragon’s. But there’s a sense here that the idea of open development was never really clarified by Epic, or solidified within the company itself. It was a utopian vision, but as is often the case with such visions, it lacked a plan on how to get there; it was a moonshot, but in a rocket built from some designs sketched on a napkin.

The community doesn’t hold the game’s demise against Epic, but it remains stranded between the nostalgia of the past and faint hopes for some kind of future for the series. At this point, the likelihood of a new Unreal Tournament game is a distant glimmer, even more remote than before the project began.