Wot I Think: Astrologaster

Forsooth, it's good

Dramatic irony: the videogame. That’s basically what you’ve got in Astrologaster. It’s a choose-your-own-tragicomedy set in Elizabethan England, where you play an astrologist and “doctor of physik” called Simon Forman, who gives his patients counsel as well as tinctures. Both his advice and potions are of questionable quality. It’s a story reminiscent of Blackadder, dripping with sarcasm, theatrical and funny. At times it doubles up as an exam in both Tudor history and star signs. And it’s sometimes a bit smug in its oh-so-literary references and knowledge. But that’s okay, because it makes plenty of poo jokes as well. I liked it a lot.

You’re an astrological quack of the 1590s (based on the real Simon Forman). After helping out London when everyone got a touch of the Plague, you find yourself in favour with the local lords and ladies, who come to you with their health concerns, among other problems. You diagnose their complaints like any good doctor would – by reading the stars.

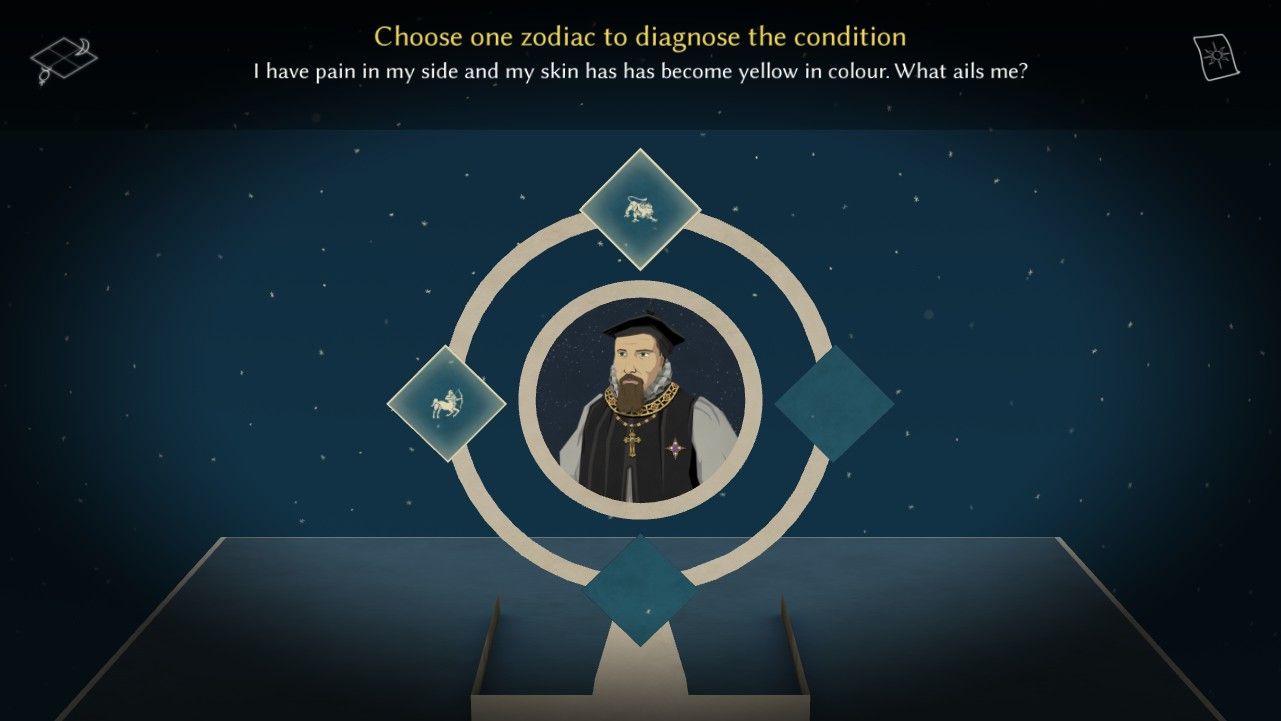

Basically, patients show up (or ‘querents’ as the Doc calls them) and they tell you about a rash or whatever, and then a pretty zodiac chart appears and you choose between two or three diagnoses. If a woman comes complaining of vomiting and headache, and she talks briefly of “celebration” in her house, one of the star signs might suggest she is pregnant. “You are with child, madam!” says Doctor Forman. At which point she’s all like: wow how did you know, the stars are powerful and wondrous. But really you just guessed the pregnancy on inference. It’s a game about divining your patients’ needs from what they say, and then using Mercury in retrograde as an excuse for giving them your “famous strong water”.

As a gamey-game, it’s very straightforward. Just a matter of clicking and swiping. The whole thing takes place in a pop-up storybook, which you flick through by dragging the mouse to flip to the next page. Basically, it’s interactive fiction with some impressive voice acting and even better singing (more on that in a second). The goal, beyond enjoying the Tudor wisecracks, is to impress your patients. Each of them have a wee meter that increases or decreases based on how much they liked your advice. Fill a character’s meter and you get a letter of recommendation. Eight of those and you can finally get that pesky medical license the College of Physicians keeps nagging you about. But Jesus, listen to me, I’m making all this sound like a dry and functional clickathon. It’s much better than that. There is singing, and the singing is good.

It’s a chorus who sing a medieval ditty about each patient who comes to visit, tongue-in-cheek harmonies that fa-la-la from the pages of this pop-up theatre. Aside from being wonderfully sung, they amuse me a lot. (I just learned that these kinds of old songs are called madrigals thanks to Jay, so now I feel smart and amused.) Each recurring visitor gets their own rhyming scheme and style. Some patients get songs like irreverent Christmas carols. Others get a proper church choir sound, grandiose hymns reserved for only the holiest Christian personages, like the Archbishop Whitgift, or the humble and blessed Dean Blague who comes to you seeking guidance. The joke lands afterwards: the Dean, it turns out, is a money-chasing asshole.

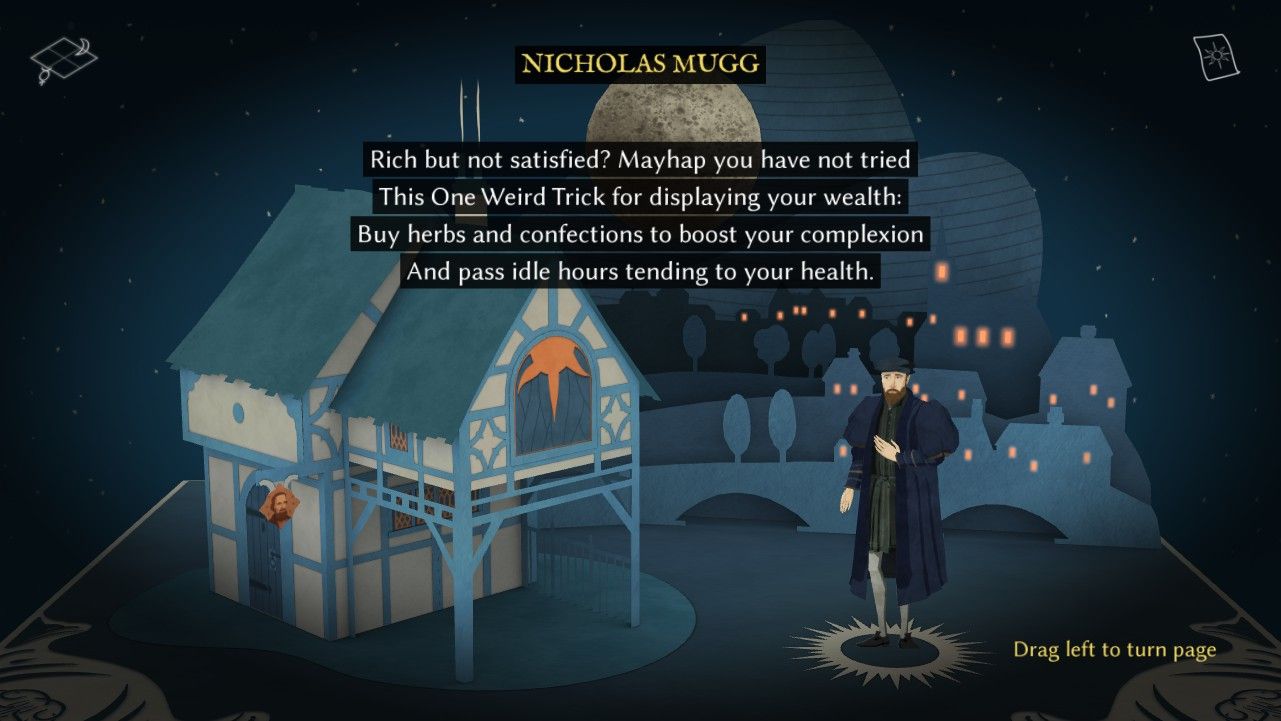

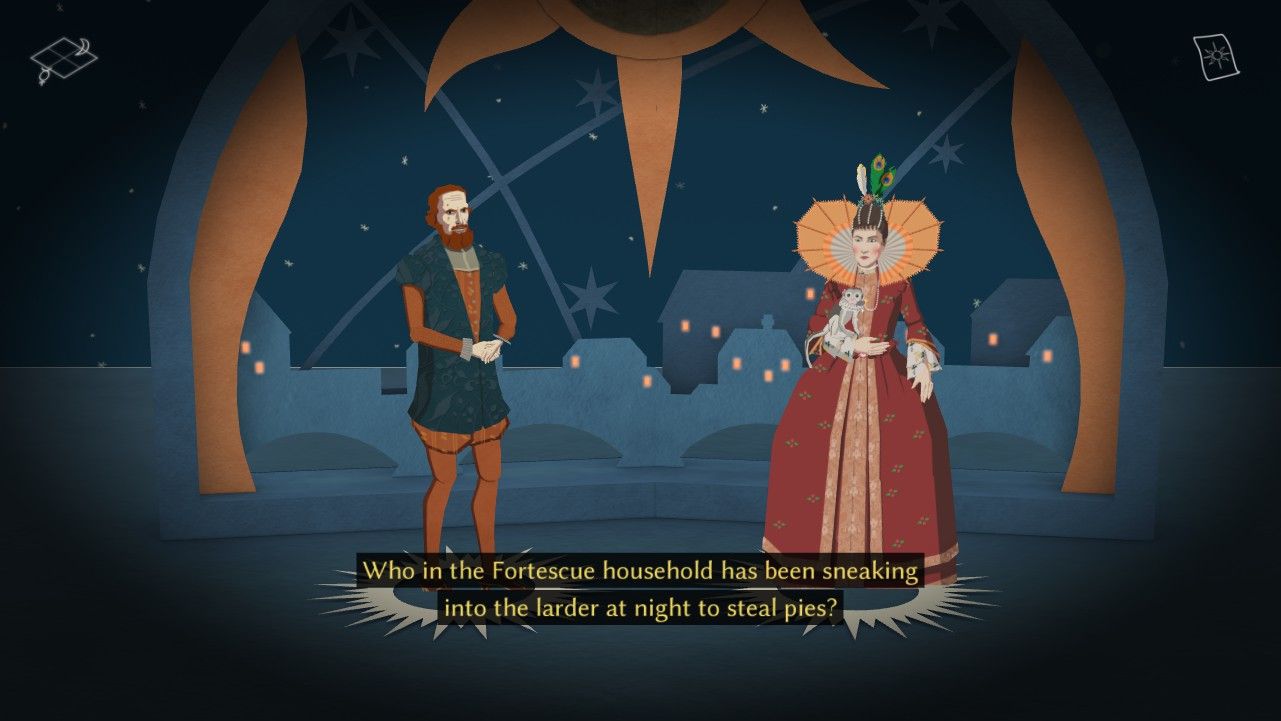

He is not the only dirtbag. Your consultations are fully voiced dialogues between doctor and a cast of sickly reprobates (and often, not even that sick). Some characters dip their bunions into the waters of sympathy, but mostly you are treating a crowd of hucksters, hypocrites, and hypochondriacs. This is a story of braggarts, liars, and fools, often hiding their true intentions under innocent queries about health, or demurely asking whether their elderly, wealthy husbands are in danger of dying soon. I love them all. On top of that, Doctor Forman, your own character, is as morally indistinct as any of his querents. And the game often lets you, as head clicker, become a chuckling force of manipulation and deception. It lets you be an absolute Puck.

There are likeable characters. Alice Blague, the hard-drinking wife of that financially reckless Dean, is constantly sleeping with other people, but she often reveals a sense of humanity underneath her chaotic sex life. Avis Allen, a woman who becomes an early regular, is the most blameless and innocent of the whole lot, and if you’ve seen any of the Shakespeare that so reliably inspires this story, you can already guess that her happiness is not in the stars.

It’s as bawdy as its inspirations too. There are jokes about “purging out of your fundament”. There are jokes about “beating off the Catholics”. Your astrological knowledge impresses one female patient to such an extent that you invite them to come see your “collection of Venetian glassware”, which is the most colourful euphemism I’ve heard in a videogame yet. This is why it reminds me of Blackadder. It makes regular gags about shagging, even as it plays with English history.

That toying with history means you’ll get more from it as a decently informed nerd of the period. It frequently probes you, seeing whether you know your Elizabethan coup attempts from your Jacobean plots, and while that might be tiresome to some players, I was happy for it to simply become another layer of dramatic irony at my expense. And there are already plenty of layers. Patients know things their husbands don’t know, the doctor knows things his patients don’t know, and you, the player, will know things the doctor doesn’t know. It’s a pyramid of dramatic irony, and depending on your own knowledge of Elizabethan history, it might be possible to become a clueless brick in that pyramid yourself.

But the important thing is that it’s funny. As a satire it also has some contemporary targets. One cocksure nobleman is shouted at by the Queen and called a “lordsplainer”. One neurotic patient always interrupts your diagnoses with opinions of his own, factoids that he has read in medical texts. He’s the Tudor equivalent of a guy who Googles his symptoms and goes to the doctor to demand treatment for the scurvy he definitely doesn’t have. Broader issues get the dagger too. The gender pay gap is jabbed at in one scene, in which a young male actor who plays women’s roles at the theatre complains he isn’t being paid as much as those actors who play men. “Be patient,” you can advise this actor, “pay equity will come in time”. Which is really blasting the dramatic irony up to post-ten levels.

Some people will probably be put off by all this self-aware clever-clogsiness. The references to Shakespeare, the nods to military campaigns gone wrong, the endless barrage of “ha ha I know something you don’t know”, the repetition of that same literary device, layer upon layer upon layer of irony, like a snarky thespian gobstopper. But I’ve always liked a smartarse, and I’d rather a smugly clever story than a boring one. I would recommend playing it in bursts though. Probably never more than a day apart, because it has such a netted cast of swine it’s easy to forget which underhanded maid is which, and who is subtextually banging who.

My major complaint is that it ends abruptly. At least, it did for me. After spending 6 hours getting to know many of these goodly clergymen and absolutely innocent widows, the game ended without telling me how many of their stories were resolved. Even Simon Forman’s own story seemed to end with the shrug of a pen nib. It’s possible I only got one of a number of endings. It’s also possible, given the game’s attitude of tittering at ignorance, that I simply need to go and read a history book to learn what really became of my good Doctor. Or at least the Wikipedia page.

But it’s a good sign that such a short game has me thirsting to know more about an obscure occultist who lived 400 years ago. In one scene, Doctor Forman admits to a patient that he merely has “the gift of logical surmise”. With that in mind (among other crimes) it would be easy to see him as the charlatan he is said to be by his enemies. But there are also moments that reveal a more complicated and conflicted man. In a short game full of haughty songs and jokes about willies, that’s an impressive achievement.