How Six Ages and King of Dragon Pass explore the politics of myth

From malevolent wizards to climate change

It wasn't till some way into development of Six Ages: Ride Like The Wind that designer David Dunham realised he was making a game about climate change. Like its 19-year-old predecessor, the seminal King of Dragon Pass, Six Ages is set in Glorantha, a fantasy universe originally cooked up by Greg Stafford, and sees you raising a community in the wilds after being expelled from your ancestral homelands. In the first game, you're fleeing the ravages of a malevolent wizard. In the second, your clan's once-proud Golden City has been swallowed up by a glacier.

With their casts of werewolves and nymphs, dinosaurs and talking ducks, neither game has much to say on the surface about present-day cultural upheavals, and they certainly weren't created for that purpose. While Dunham argues that most games have a political dimension, he's unconvinced by “message games” that trade nuance for impact. The theme of displacement by a disaster is in some ways just a designer's dodge, “a convenient excuse to start you off poor and working your way up”, and the parallel in Six Ages with the contemporary effects of global warming is entirely accidental: “it just happened that that was what was going on in Glorantha's Mythic Era, at the time.” Nonetheless, Dunham admits to “nurturing” the comparison as work on the new game continued. “The root cause of your migration is still an issue, so you’ll meet other refugees from the Golden City during the game,” he says. “None of this was intended as political commentary, but it’s easy to get a message.”

King of Dragon Pass has, of course, long been celebrated for its blend of choose-your-own-adventure storytelling and social simulation. It's a game that brings an unfamiliar warmth to dusty matters of crop production or whether your burgeoning settlement needs a watchtower - lashing these elements to a series of beautifully illustrated, open-ended narrative episodes that range from chasing off wolves to feasting the ghosts of the departed. But if there's a reason to play it and Six Ages right now, in the age of Brexit, soaring temperatures and Trumpism, it's for how they interrogate the insecurities and phantasms at the heart of nationhood. They are games about the shifting boundary around any community, a boundary both tangible and comprised of the histories and myths each community dreams up to explain its place in the universe, weather catastrophes and keep outsiders at bay. “Social cohesion is actually a huge deal in both games,” notes Dunham. “It’s probably one of the big roleplaying aspects, in that you’re playing a culture where exile is the worst punishment.”

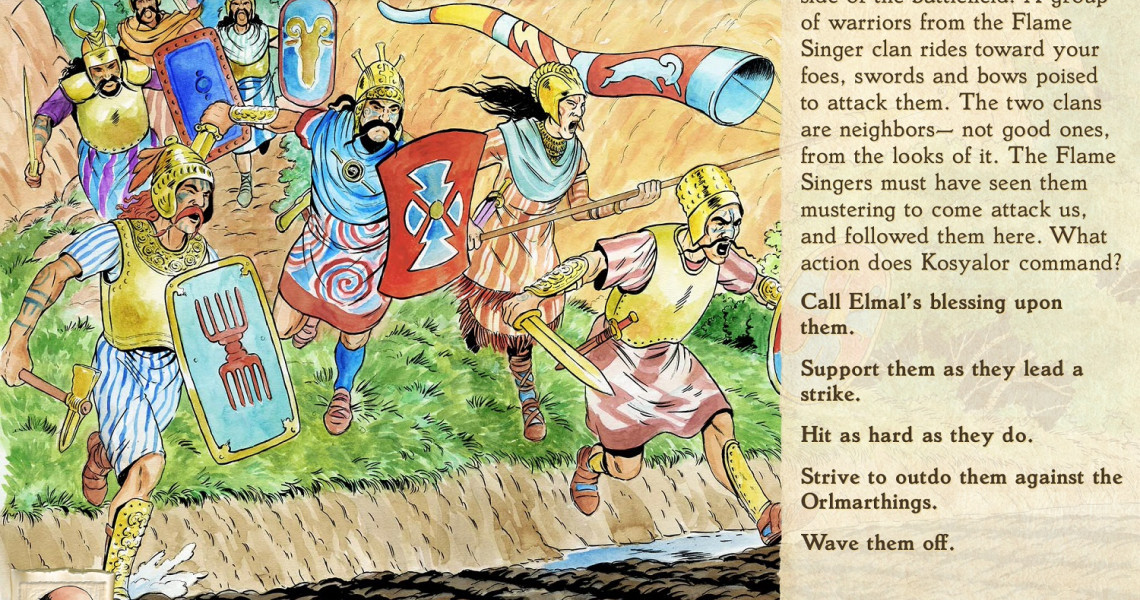

These dynamics inform the broader economic and strategic rhythms of each game, which see you jostling for land, cattle, goods and divine favour with a host of rival clans. They also shape the smaller events and choices you'll deal with when not preoccupied with the state of your military or food reserves, all of which feed into the world map's bubbling politics and breed additional encounters down the road. Many of these episodes are simply about who you let into the fold and who you send packing. Your followers may have misgivings about welcoming a hatchet-faced outlaw, for example, but they might be prepared to accept her child, if only because babies carried into town on shields by mysterious hermits tend to lead more interesting lives than, say, kids who grew up hitting pigs with sticks.

You'll also be called on to handle the delicate question of a love affair outside your clan, and tackle racism in the shape of antipathy for nonhuman species. If you're the ogreish type, you might choose to exploit clanless wanderers, confiscating their possessions without fear of anybody seeking redress. “We use the term “outlaw” in its literal sense - you are outside the protection of the law, of your community,” says Dunham.

Aiding and abetting you throughout all this are your clan's advisers, characters of different ages and genders whose portraits appear on every menu, ready to share their wisdom or at least, push their agendas. Sometimes they'll offer helpful advice, reminding you that half your weaponthanes are off sick just as you're about to wage war on your cuddly neighbours, the Thunder Ducs. Other times they'll bend your ear on behalf of the god they worship, or treat you to a smug proverb. The advisers compare to hero characters in certain 4X games, in that you can send them on errands like sweet-talking a chief you're keen to trade with. But their real value with regard to each game's broader artistic achievement is that they keep the collective self-image of your clan in view, never letting you forget that each incident is part of the story your community is at once constructing and living out.

The idea that societies are essentially narrative entities, tales that evolve in the retelling rather than mere grab-bags of territory or property, is everywhere in KoDP and Six Ages. Where many social management sims occupy a kind of endless, top-down purgatory limited only by the resources available or your attention span, these games are much more about changes in time than space. The cycle of seasons, for instance, is probably the greatest single influence on your activities as leader – it's foolish to go raiding early in the year when your farmers should be planting crops, or send out explorers in the depths of winter. And then there's the issue of mortality, with characters (including advisers) ageing and dying as the years wear on. “I really wanted to do a sort of family saga, kind of like Greg Stafford's Pendragon campaign that lasted 75 years, where you'd see characters grow up and die of old age, just like in Icelandic sagas,” Dunham comments. “The hero's parents start the game, and then his children end the story burying the hero.”

The process of generation giving way to generation is where each game's interrogation of the social function of storytelling comes to a head. When you start a game of KoDP or Six Ages you'll answer a questionnaire to fill out an origin story, similar to the character generation sequences of RPGs like Mass Effect. The options range from deciding whether your ancestors were slave owners through how they celebrated certain points of scripture to whether they were on good terms with dragons. All of them confer bonuses, but they also make it tricky to follow different paths for fear of annoying the watchful spirits of your forebears. You'll be expected, for example, to maintain enmity with anybody the old folk didn't get on with, or else contend with an exhilarating variety of curses.

On the flipside, you can also cynically exploit the founding myths of neighbouring clans to get the upper hand in negotiations. If a rival clan is traditionally affiliated by a certain god, they're more likely to be swayed if you bring up said god's making a cardinal virtue of generosity. And then there's the process of winning the game in KoDP, whereby you must painstakingly learn, then re-enact the deeds of various deities, making their legends your own. Victory, in other words, isn't a question of conquest or cranking out points: it's about demonstrating your familiarity with the narratives that are the true bedrock of this realm.

The result is a complex meditation on myth as on the one hand a unifier, keeping societies afloat amid disaster, and on the other as a reactionary element, a sacrificing of the future on the altar of the past. Dunham references the resurgence of fascism today, offering a distinction between “true” myths that empower without foreclosing alternatives and “the constructed story, the false myth” that is wielded to divide and destroy. “If you can only read a myth one way, then it's not a very good myth,” he suggests.

You could argue that Six Ages doesn't add much to what King of Dragon Pass achieved on this front back in 1999. The game won't see a PC release till 2019, but a few hours with the iOS version suggests that it's more a question of tidying up than reinventing wheels: the clan dashboard screen makes more information obvious at a glance, and while story episodes are still a question of informed guesswork, advisors spend more time explaining what went wrong when a decision backfires. Dunham acknowledges the influence of Failbetter's literary sims on the new game's more restrained spread of choices per story scene, conceding that KoDP went overboard on this front. “It isn't easy to give you lots of choices that are all of equal weight, none of which are supposed to be right or wrong. Fallen London and Sunless Sea usually don't give you that many responses, and it works totally well.”

If Six Ages is more of a retread than a sequel, however, it's a return to themes that have only grown more pressing over the intervening decades. We live in an era of unprecedented disruption, with hundreds of thousands of people cast into the road by war, injustice and the mounting fallout from global warming, and also an era of hardening attitudes, as fears about the 'dilution' of native cultures by migrants propel demagogues into office. Games like King of Dragon Pass may not be explicit critiques of our historical moment, but they are useful resources when it comes to understanding the role myths and fantasies of all kinds may serve in closing these divides - or widening them.

King of Dragon Pass is one of our 50 best PC strategy games ever in the history of ever. Fancy that.