Wot I Think: Orwell - Ignorance Is Strength Chapter 1

Orwell: Ignorance Is Strength is being released, for some odd reason, in three chapters over the space of a month. The first is out now, and so I put on my best spying monocle to tell you wot I think.

Orwell was a game I thoroughly enjoyed despite its ludicrously silly conceit - a day one appointee at a secret government spying programme being given the reins to investigate a serious terrorist attack. So, with the arrival of its sequel, I hoped it was at least in a position to move on past this daft premise. But, no! Amazingly, you're yet again someone who's applying online to work for Orwell, and that same day you're given access to techno-spying abilities that shouldn't be in the hands of MI5's highest ranking operatives.

When I reviewed the first game, I realised I was in the odd position of having this arm-long list of things that made the game seem fundamentally silly, but argued for how I'd enjoyed it so much despite that. In playing the sequel just over a year later, I'd really hoped to be saying how so much of these daft problems had been addressed, and that which made it such a good idea be pushed to the front. Unfortunately, not a single aspect of its conceit has changed.

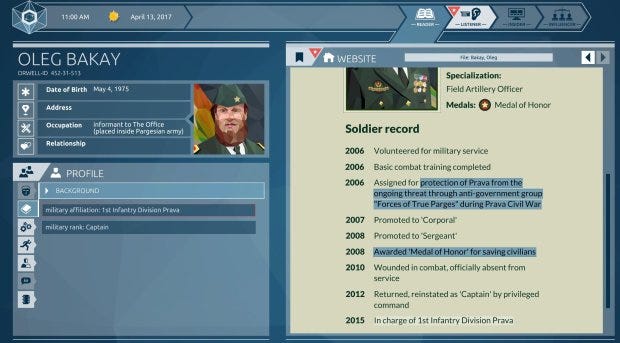

The silly takes the form of the Orwell system, a means of government spying where they give day-one recruits access to unimaginably powerful spying equipment (just knowing someone's email address means you can immediately read their incoming and outgoing mail, for instance), but those same recruits have no access to Google. Your handler, meanwhile, isn't allowed access to all these materials, but only the information you send her. The rationale that the first game used was something to do with prevention of invasions of privacy by government officials. Like I say, silly. As you try to find connections between people involved in potentially anti-government situations, you unearth websites and blogs and faux-Twitter accounts ("Blabber", here), but only by stumbling upon references to them in the previous item. It's a bizarre and nonsensical way to go about investigating an individual, but not nearly as daft as the means by which you communicate your discoveries.

Only certain details, words or sentences that you find can be dragged onto an individual's profile. Some (very few) are irrelevant, some are colour to the story, and some are crucial to opening up the next stage of the game. Amongst these are so-called contradictions, yellow-highlighted pieces of information that are countered by another fact in your findings, and which of these two you choose to pass on to your handler determines how she understands the case, and the unfolding of the overall story. That's the part where it got interesting last time, where it was worthwhile replaying to see how else events might have occurred, but it was also the most undermining aspect of the game, too. Because the game will alert you that something is a contradiction before you've found the "data chunk" that contradicts it. The system tells you that the conflicting information has yet to be uncovered... So it already knows about it, but isn't showing it to you because - I've got nothing.

All of that I forgave last time, because the concept felt novel and fun despite it all. You were spying on people, and it felt cool, and as you explored the tale you began to see the grey and started to realise how you could manipulate it. This time, it's not novel. In fact, it's the same as last time, only it feels even more contrived. Last time you were investigating potential suspects of a terrorist attack. This time it's about investigating the author of an anti-government website who might or might not be involved in the disappearance of a military captain from a foreign army. You're devoting all of these tremendous resources into looking into some guy who writes a blog.

The idea, I think, is to drive home the point that you're potentially working for a corrupt system, and this guy is, perhaps, being targeted more for his counter-information campaign than any realistic chance of his involvement - whether he's guilty or not. But that feels so heavy-handed, so on the nose, that it dispels with any notion of the subtlety of Orwell's previous outing. And even when the details start to spill out into something slightly more involved, I still felt no interesting connection to the events.

More problematic, the system itself didn't seem to make sense. Last time you got a good feel for what information was vital, what would deliberately skew your handler's perception, and what was noise. But this time I couldn't tell incidental nothing from the vital clue that would allow the story to continue. At one point I'd reached a dead end because I didn't pass on some banal fact that I thought irrelevant to the case.

This is the first of three chapters, to be released in relatively quick succession - the rest of the game will have come out by the end of March - and we're told that the second two parts will feature new aspects to the Orwell software that we didn't have before. But that has the effect of meaning our opening return to the game's world is blandly similar, with a far less interesting story, and no new surprises. It's also, as a result of this seemingly pointless fracturing of the release, incredibly short.

I don't understand the logic of breaking a small game up and then releasing it within the same 30 days. There's a decent chance that the elements introduced in Chapters 2 and 3 (March 8th and 22nd) will elaborate this into something far more gripping and involved, and I'll eventually look back at this first chapter as a slow start. But by using this peculiar release method, all the emphasis is on a fussy and ultimately not very interesting introduction. So hold your horses for the moment, is my tip, and hopefully in a month's time I'll be back with a far more positive recommendation.

Orwell: Ignorance Is Strength is out now at £7/$9/9€ for Windows, Mac and Linux, via Steam, GOG and Humble.