Phantom Doctrine is much more than a Cold War XCOM

(Under)cover-based

Phantom Doctrine is a game of 'ifs' and 'buts'. I would have completed my mission without being spotted if one of my agents hadn't been compromised but the fact that she turned on me and I managed to neutralise her at least means the enemy has played their hand and she can't do any further damage. Now, even though our cover is blown, if we can make it to the extraction point this will still be a success.

But I'm really tempted to leave one member of my team behind if he keeps attracting the attention of guards and...oh, now there's a helicopter and we're apparently troublesome enough that missile strikes are an option. I am a bad spy.

This is the game that won my heart at Gamescom earlier in the year. It's always a risk, falling for a game before having a chance to play it, but as I wrote at the time, it “looks like an exquisite marriage of setting, mechanics and theme”. Think XCOM but with shadowy and very human conspiracies rather than extraterrestrial invaders, and a cold war setting that draws on seventies thrillers to introduce such delights as brainwashed double agents, chemically-enhanced soldier-spies, and enough secrets, lies and betrayals to fill every Christmas soap opera episode from here to 2052.

Also murders.

Now I have played it, though I spent most of my time getting into trouble on a tactical mission rather than blowing conspiracies wide open on the strategic map. What I've learned is that the XCOM comparison can only take us so far. There's a world map and a hideout base where soldiers are recruited/promoted and where interrogations occur. There are isometric tactical missions with a UI that'll make sense to anyone who has spent time with Firaxis' aliens, but for everything that seems immediately familiar, there are new and unusual elements. And, in fitting with the conspiracy-themed setting, nothing is quite as it seems.

Your ultimate goal is to unpick a plot that sees East played against West. You're not working for either side, but rather trying to bring down a third-party who are playing everyone off against everyone else. That means you're outgunned and outnumbered, because you're often forced to infiltrate embassies and go up against governments against secret agencies who are themselves pawns in a larger scheme.

The small group of agents that you control are seen as enemies by everyone, essentially framed as villains and terrorists as they try to prevent a global cataastrophe. You're up against the whole world, and that's why you need to play smart.

Brute force isn't going to get you anywhere and when I had to resort to shooting my way out during a scripted plot mission, as soon as the alarm was triggered, an endless supply of guards appeared at the borders of the map. Every turn, new squads, and eventually that helicopter, which targets agents forcing them to flee for cover or be blown to bits. There are probably missions where an aggressive approach does pay off, but for the most part this is tactical stealth.

That means line of sight is important, as is paying attention to areas of the map that are off limits. I was able to put my agents into position outside the installation they were preparing to enter and they were treated as harmless civilians as long as they were on the outside and didn't do anything suspicious. Like cracking the neck of a guard or firing a weapon.

When we did crack a couple of necks, bodies were easily disposed of before anyone could spot them, and we managed to get inside. And once inside we met up with the fourth member of our group, who had been embedded before the mission began.

That's one of those unexpected elements. There are essentially three possible start-points for agents on a mission. They can be part of your squad, preparing to infiltrate, they can be planted within the objective by assigning them to go undercover on the world map, or they can be at the perimeter of the map working as spotters or snipers. Those latter agents can't enter the actual tactical grid – they're off-screen, assigned to one edge of the map and equipped with either a scope or a rifle. With the scope, they can track enemy positions, and with a rifle they can pick off anyone foolish enough to stand near a window or in the open.

And the undercover agents can do just about anything you might imagine. You could have them kill all of their 'colleagues' silently and efficiently, giving your other agents a clear path to their target (whether that's documents to steal, systems to sabotage, or a person to kill or kidnap), or they could simply act as eyes and ears on the inside. It might even be possible to have them complete objectives while pretending to be a good employee, without drawing attention to themselves.

Just because they're on the inside, that doesn't mean they'll have clearance for every building or room on-site though and even the best disguise can be undone in one careless moment. Imagine this Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy scene but turn-based.

Tension is the key to it all. In most tactical games, cover is a waist-high wall, a tree trunk or the corner of a building; here, before it's any of those things, it's an espionage concept. Rather than being the place that you cower when the bullets start to fly, cover is the thing you try to preserve to avoid a firefight.

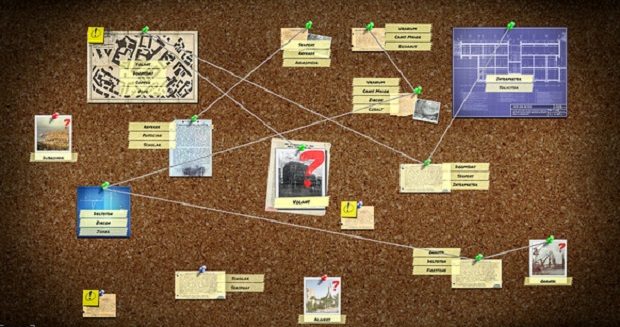

All of that feeds from the tactical encounters to the world map. As situations arose around the globe, I'd dispatch agents, alone or in groups, to find out what the hell was happening. Sometimes they discover an enemy agent or a specific plot, which can open up new avenues of investigation that might eventually lead to a set mission that moves the core narrative along. Sometimes they find information that can be applied to the big conspiracy board, where you make links between places and people and scraps of intercepted data in the most gloriously low-tech way possible. It's pinboards and string, and it's fantastic.

The information board is an example of Phantom Doctrine communicating its theme perfectly. It's not all that complicated – you're effectively looking for words that match across various scraps of paper – but the text on each document feels like it's been plucked out of any one of the 1970s thrillers that are as much an influence on the developers as XCOM or Invisible, Inc. Redacted phrases are used cleverly to break up sentences and paragraphs so that gaps in the logic of the generated text are literally painted over.

I didn't have a chance to play with the wider campaign enough to say for sure that it will work. Brainwashing and then releasing enemy agents, so they can be flipped to your side during a later mission, is great, and I have high hopes for the chicanery all of that manipulation will make possible. But there are a lot of overlapping systems through the different layers of the strategic map and the tactical confrontations. Speaking to the developers, it's clear that they are, at one level, attempting to provide a balance between proactive and reactive play, something that XCOM has grappled with to some success.

Here, you can go for the throat of the conspiracy and use hit and run tactics to kick the hornet's nest, or you can be more subtle, tinkering with the knowledge you've found to defuse situations before they explode into violence. It's a bold game, built on the premise that information is power and then giving the player ways to uncover that information and deploy it as the see fit.

The closer you look, the less of XCOM there is to see. It's the machinery beneath the surface that makes Phantom Doctrine tick and I reckon it's complex enough that I'll enjoy getting my hands dirty and picking it apart.