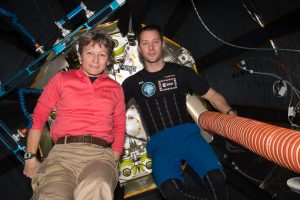

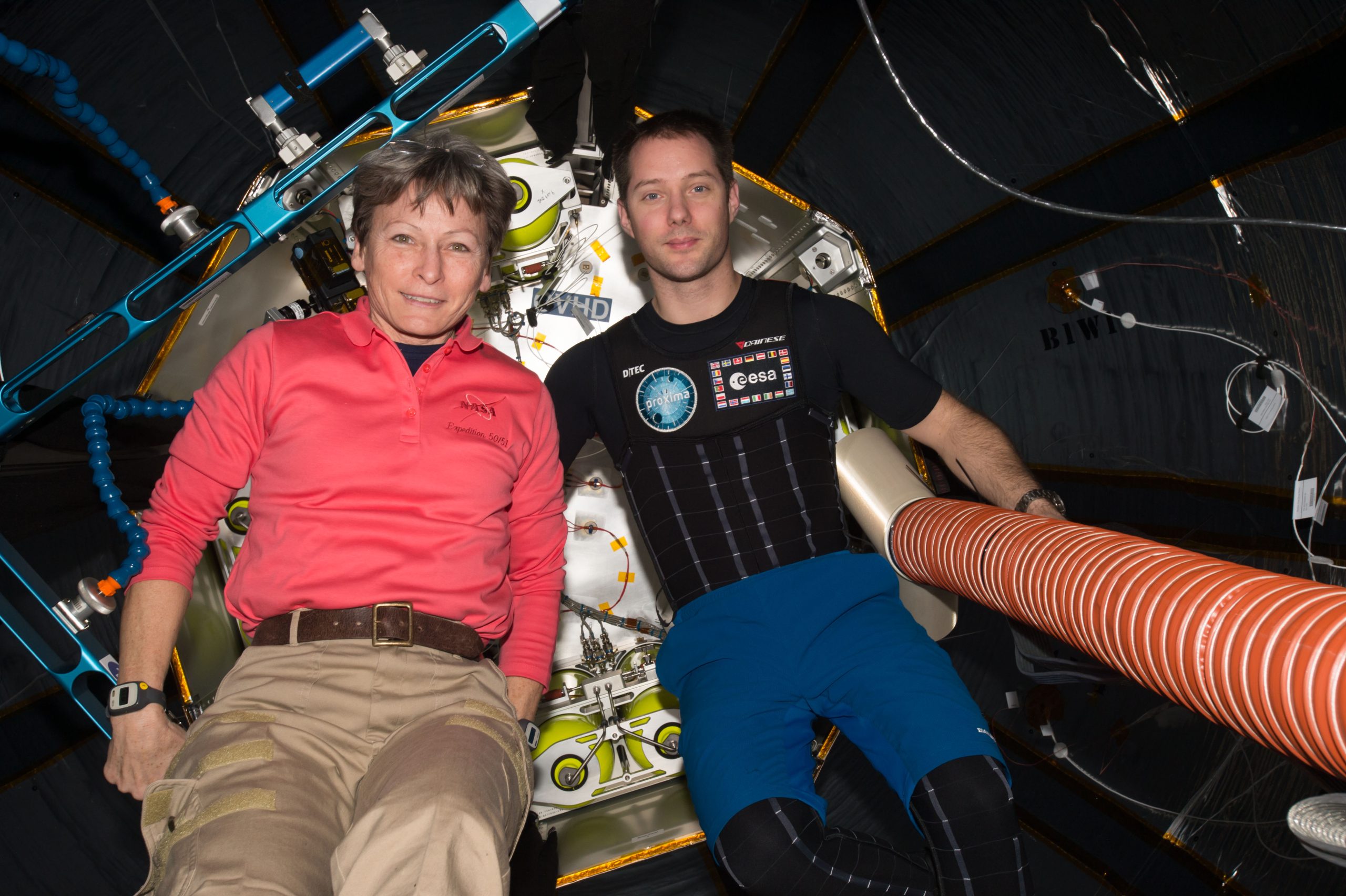

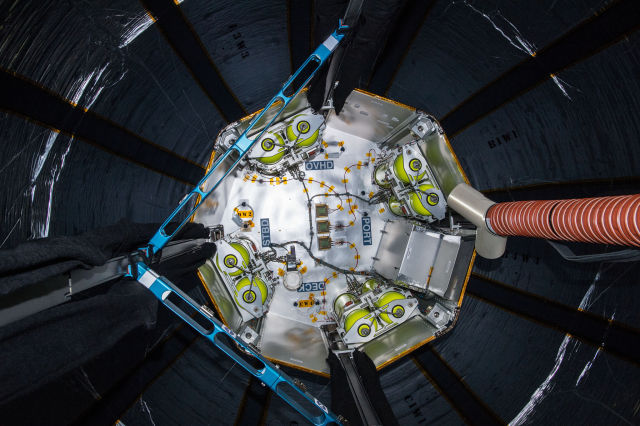

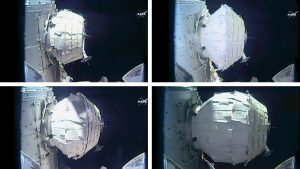

It has now been a year since NASA successfully expanded a habitat attached to the International Space Station, the experimental Bigelow Expandable Activity Module. Initial tests on the module suggest that expandable habitats may play an important role as NASA considers how best to expand human activity into deep space.

During the first year, NASA and its astronauts on board the station have sought primarily to test the module's ability to withstand space debris—as a rapidly depressurized habitat would be a bad thing in space. And indeed, sensors inside the module have recorded "a few probable" impacts from micrometeoroid debris strikes, according to NASA's Langley Research Center. Fortunately, the module's multiple layers of kevlar-like weave have prevented any penetration by the debris.

While NASA will continue to monitor the module for debris, the agency's focus is now turning toward radiation. Bigelow officials have said the company's inflatable habitats should be as good as, or better than, the space station in terms of limiting radiation. Unlike the station’s metallic shell, which scatters radiation from solar flares, the non-metallic skin of the expandable module should reduce this scattering effect.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...