October is LGBTQ History Month, and to celebrate, NBC News will feature an NBC Out weekly review of key moments and people in LGBTQ history. Each week’s feature will include images from the New York Public Library’s LGBTQ archives. This week, we look back at the early days of the AIDS epidemic in America.

A LURKING VIRUS

When the AIDS plague finally took hold in the U.S., it surged through communities that the straight world preferred not to see.

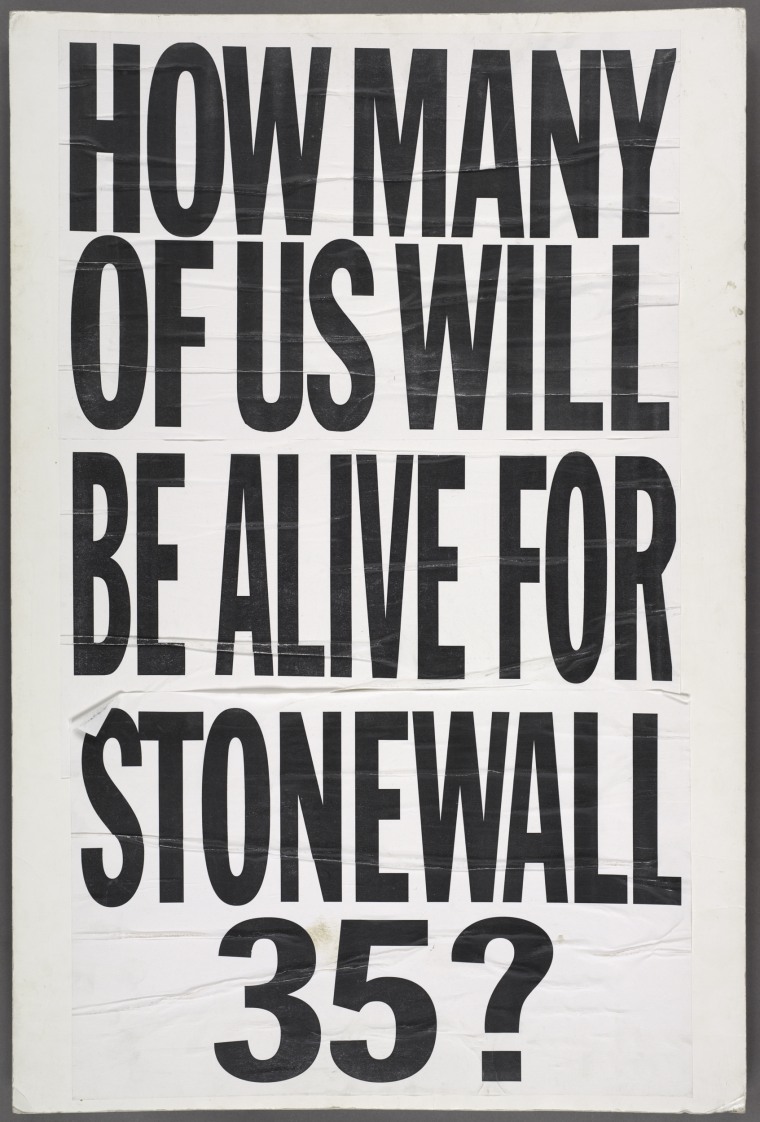

It took a few tries. The virus lurked in tropical regions of central Africa, and made several incursions into the American continent before becoming a global pandemic. HIV likely killed a young man in St. Louis in 1969, just one month before the Stonewall riots. A Norwegian sailor died from AIDS in 1976 after he likely contracted the virus while traveling in Africa.

It was not until the late 1970s when the HIV strain that started the North American pandemic had made its way to the United States, via Zaire and Haiti. By then, the sexual revolution was in full swing and HIV was spreading silently among gay male populations in large American cities. Men who have sex with men were, and still are, disproportionately impacted by HIV because it transmits much more easily through anal sex than through vaginal sex.

The first official government report on AIDS came on June 5, 1981, in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, a government bulletin on perplexing disease cases: “In the period October 1980-May 1981, 5 young men, all active homosexuals, were treated for biopsy-confirmed Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia at 3 different hospitals in Los Angeles, California. Two of the patients died.”

In NBC Nightly News’ first report on AIDS in June 1982, Robert Bazell reported that “the best guess is some infectious agent is causing it.”

In a 1983 appearance on NBC's "Today" show, activist and Gay Mens Health Crisis co-founder Larry Kramer asked host Jane Pauley, "Jane, can you imagine what it must be like if you had lost 20 of your friends in the last 18 months?"

"No," Pauley replied.

"It's a very angry community," Kramer said.

Even as the nation's attention was directed toward gay AIDS victims, the virus was replicating in the bloodstreams of hemophiliacs and injection drug users. A government report from August 2016 found that between the start of the AIDS epidemic and today, nearly 700,000 people have died of AIDS in the U.S.

THE 'GAY PLAGUE'

After the Stonewall Riots in 1969, LGBTQ activists across the country made significant civil rights advances and secured some municipal and state-level protections against discrimination in public employment. Roughly two dozen states had decriminalized sodomy by 1980, and some activists were already talking about the next frontier: legal recognition for marriage.

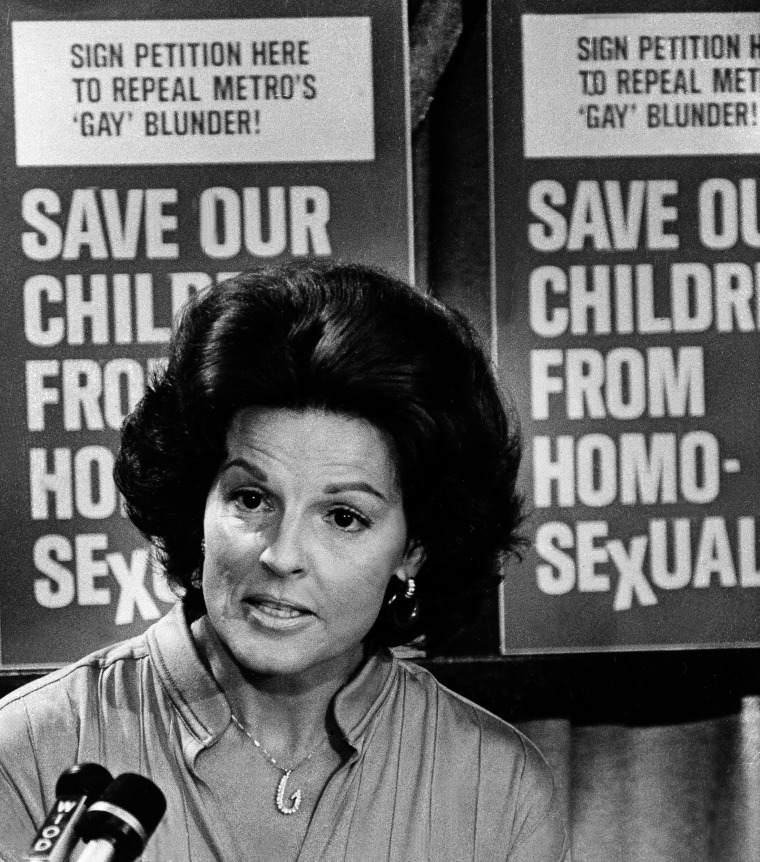

Almost at the exact time that HIV cases first began to pop up in Los Angeles and New York, the LGBTQ civil rights struggle faced a reactionary backlash led by figures like Anita Bryant and Rev. Jerry Falwell, whose “Moral Majority” inveighed against giving rights to gay people.

On March 22, 1980, a year before that first MMWR report, evangelical Christian leaders delivered a petition to President Jimmy Carter demanding a halt to the advance of gay rights. “God’s judgment is going to fall on America as on other societies that allowed homosexuality to become a protected way of life,” Bob Jones III predicted, according to UPI.

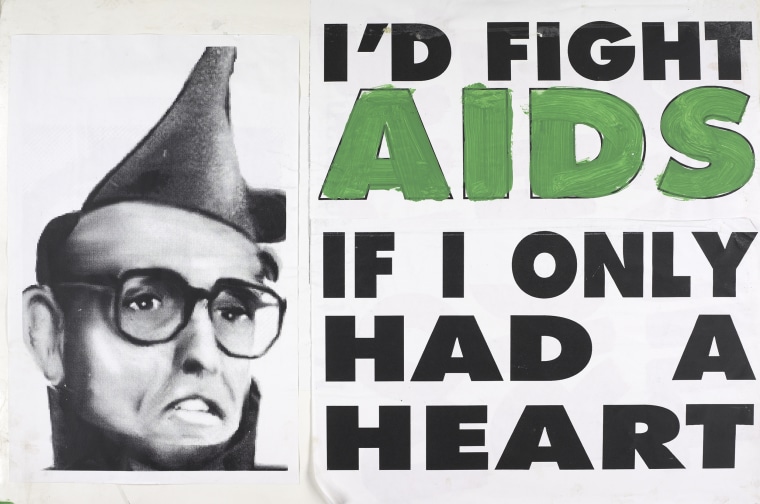

As the anti-gay reaction gained steam across America with the election of Moral Majority ally Ronald Reagan, activists found their demands for attention for a growing medical crisis were ignored. The march for LGBTQ civil rights ground to a halt — after more than a dozen states repealed sodomy bans in the 1970s, just two jurisdictions, Wisconsin and the Virgin Islands, decriminalized sodomy in the 1980s.

In 1982, Larry Speakes, press secretary for Reagan, laughed when asked about whether the president was tracking the spread of AIDS.

“It’s known as gay plague,” the journalist asked. Some people in the room chuckled.

“I don’t have it, do you?” Speakes snapped back, as the room erupted in laughter. "Do you? You didn't answer my question. How do you know?"

In 1984, Health and Human Services Secretary Margaret Heckler announced the discovery of the virus that caused AIDS, the development of an AIDS test, and forecast that a vaccine would be available by 1986. But no vaccine ever came.

'SEIZE THE FDA'

After Heckler’s announcement, it took a year before Reagan publicly uttered the word “AIDS” until 1985, when over 12,000 Americans had died and the virus had begun to spread swiftly through hemophiliac populations and injection drug users.

In 1987, zidovudine, or AZT, became the first drug approved to treat AIDS. But the drug only seemed to slow the progression of the disease, and did not cure it or even prevent death. Patients were prescribed to take an AZT pill every four hours, night and day, forever. Today, we know that this amount of AZT is a toxic overdose.

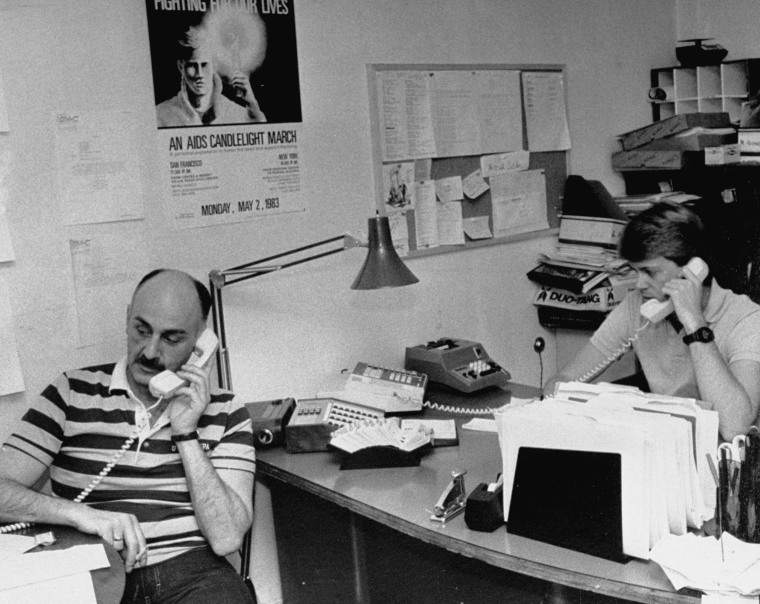

In the face of government silence, and in the absence of a promised vaccine, AIDS activists began to organize to provide care for the patients who were falling ill. One such group was the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, founded in New York City in 1982, which is today the oldest HIV/AIDS service organization in the world.

But in 1987, activists were still frustrated by government inaction as bodies continued to pile up, and they founded the AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power, or ACT UP, in New York City.

Today, their actions and their activist art are legendary for speeding the government’s response to the AIDS crisis, allowing quicker testing and treatment of lifesaving experimental drugs, and drawing public attention to the deadly impact of homophobic public health policies.

“Our first demonstration [took] place three weeks later on March 24 on Wall Street, the financial center of the world, to protest the profiteering of pharmaceutical companies,” ACT UP wrote. In particular, the sky-high price of AZT: $10,000 per year.

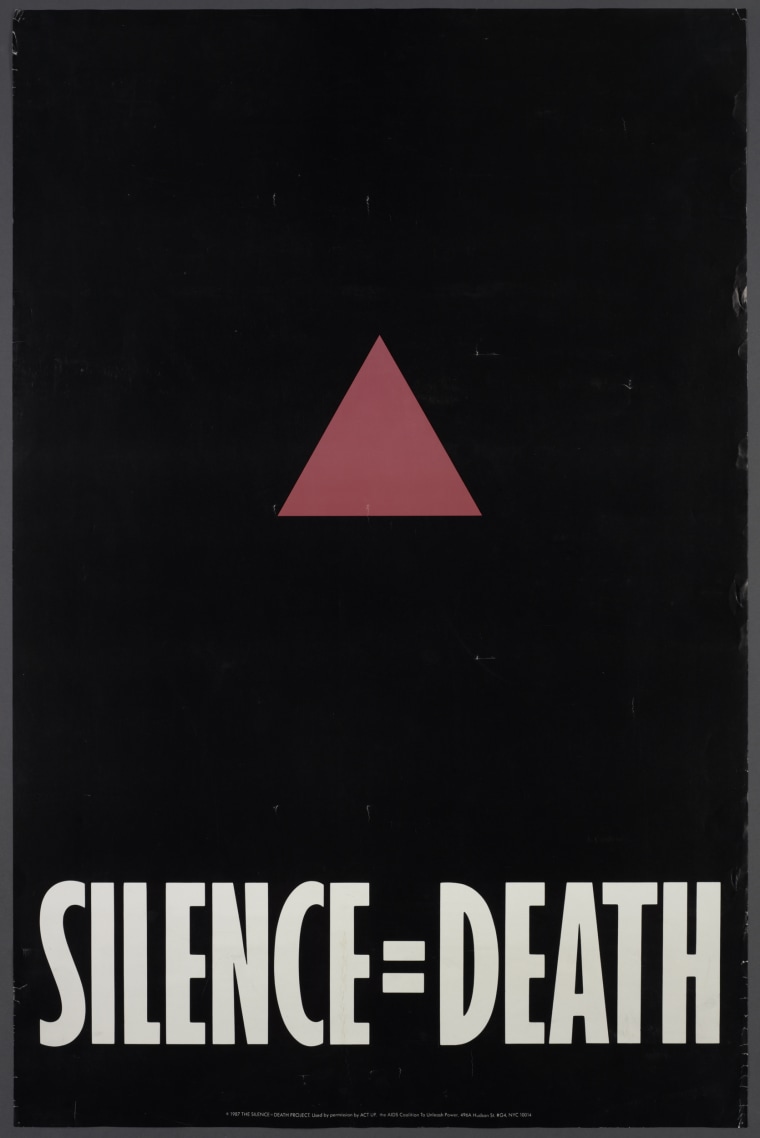

Avram Finkelstein, one of the designers of the iconic ACT UP poster “Silence=Death,” wrote in guest post for the New York Public Library:

"In 1981, my soul mate started showing signs of immunosuppression, before AIDS even had its name. By 1984, he was dead, a year before Rock Hudson had been outed by the disease and died, and Reagan had uttered the word. This private devastation compelled me to form a collective with two of my friends."

Finkelstein continued: "And in order to 'sell' activism in an apolitical moment, the poster needed to be cool, and to intone 'knowing.' It needed to be both rarified and vernacular at the same time. It needed to give the impression of ubiquity, and to create its own literacy. It needed to insinuate itself into being. It needed to be advertising."

ACT UP activist Douglas Crimp, writing in The Atlantic, said the October 1988 action "Seize the FDA" was a turning point that “occurred for two interrelated reasons: 1) the demonstrated knowledge by AIDS activists of every detail of the complex FDA drug approval process, and 2) a professionally designed campaign that prepared the media to convey our treatment issues to the public.”

“ACT UP's fundamental contention was that, with a new epidemic disease such as AIDS, testing experimental new therapies is itself a form of health care and that access to health care must be everyone's right,” Crimp wrote.

ACT UP activists continued to stage ever more dramatic operations to draw national media attention toward AIDS. In New York, in December 1989 ACT UP and took over St Patrick’s Cathedral.

In 1991, Activist Peter Staley draped a giant condom over the home of noted homophobic senator Jesse Helms from North Carolina.

A LEADING KILLER

By 1995, AIDS was the single greatest killer of men ages 25-44 in America and millions more around the world were infected. It was also the year the government approved the first protease inhibitors, a class of antiretroviral drug that, when combined with existing therapies, proved effective enough to halt and reverse the progression of the disease.

After years of toxic HIV treatments of varying efficacy, AIDS was over — but only for those who could afford it. The burden of the epidemic began to slide toward the poorest and least connected to health care. Today, HIV thrives in the poorest regions of America, like the Mississippi Delta.

In 1996, for the first time, AIDS deaths dropped by 23 percent. But that year, African-Americans for the first time comprised a greater share of HIV diagnoses than whites — despite the fact that the minority group is significantly smaller.

In 2003, President George W. Bush enacted perhaps the most consequential program of his presidency: the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, or PEPFAR, which buys and distributes life-saving HIV medications to poor people around the world. It is the largest ever government program devoted to fighting a single disease — 14 million are on treatment today because of it.

U=U

In 2008, the Swiss government released a statement of scientific consensus affirming something that had long been theorized but never proven: HIV positive people who are virally suppressed from taking effective HIV drugs cannot transmit the virus to HIV negative people. The shorthand version of this new paradigm has been embraced by the United Nations and the United States: U=U, or "undetectable equals untransmittable."

The “Swiss Statement” revolutionized how clinicians deliver HIV care around the world, and began to shift treatment from “wait and see” to “test and treat” — meaning people who test positive today usually begin taking medications immediately, for their own benefit and for the public’s benefit as well.

Then in 2012, scientists publish data showing that a once-daily Truvada pill could significantly reduce the possibility of HIV transmission, which is today known as PrEP, or pre-exposure prophylaxis. While this treatment was controversial when introduced, it is today growing in popularity and responsible for drops in HIV rates in large cities like San Francisco, New York and Washington, all of which have funded robust PrEP programs.

On Dec. 1, 2016, the New York City AIDS Memorial was unveiled across from St. Vincent's Hospital, once the epicenter of the North American AIDS epidemic. It is dedicated to the 100,000+ men, women, and children who died from AIDS in New York City.

As of 2017, the AIDS epidemic has infected an estimated 77 million people globally and killed 35 million, according to UNAIDS. The organization estimates there are currently 37 million people living with HIV around the world.