By Richard McKenna / March 27, 2017

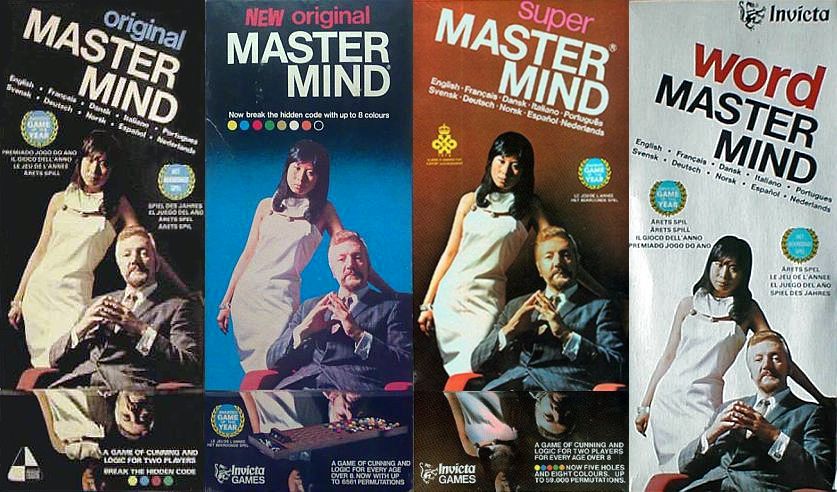

Back before the adults of the Western World depended almost exclusively upon digital sprites for their entertainment and began dressing up as toys and cartoons, one of the world’s most popular games was synonymous with the image of an immaculately groomed, middle-aged Caucasian man and a beautiful Asian woman. Fingers steepled, he sat staring condescendingly down his nose at us, his potential opponents, while she stood behind him, regarding us with enigmatic detachment. Both their figures were reflected (and thus, due to the angle, inverted) in what appeared to be a glass boardroom table. Pulsing with the echoes of colonialism, the scene bore with it the sulfuric whiff of sinister international glamor, intrigue, wealth, the incomprehensible logistics of multimillion dollar agreements, and espionage. Adding to the cover’s gravitas were the various combinations of awards the game had won: the Game of the Year laurels, the prestigious black and white triangle of the Council of Industrial Design’s award, and the Queen’s Award for Export Achievement, as well as an intimidating list of the languages that the instructions came in, all conferring upon it an aura that bespoke international trade success as much as it did after-tea fun.

Back before the adults of the Western World depended almost exclusively upon digital sprites for their entertainment and began dressing up as toys and cartoons, one of the world’s most popular games was synonymous with the image of an immaculately groomed, middle-aged Caucasian man and a beautiful Asian woman. Fingers steepled, he sat staring condescendingly down his nose at us, his potential opponents, while she stood behind him, regarding us with enigmatic detachment. Both their figures were reflected (and thus, due to the angle, inverted) in what appeared to be a glass boardroom table. Pulsing with the echoes of colonialism, the scene bore with it the sulfuric whiff of sinister international glamor, intrigue, wealth, the incomprehensible logistics of multimillion dollar agreements, and espionage. Adding to the cover’s gravitas were the various combinations of awards the game had won: the Game of the Year laurels, the prestigious black and white triangle of the Council of Industrial Design’s award, and the Queen’s Award for Export Achievement, as well as an intimidating list of the languages that the instructions came in, all conferring upon it an aura that bespoke international trade success as much as it did after-tea fun.

The game was Mastermind. Resembling a much earlier pen-and-paper game called Bulls and Cows (which originated in Britain), Mastermind was the brainchild of Romanian-born Mordecai Meirowitz. After trying unsuccessfully for several years to interest toy companies in his product, Meirowitz—a postmaster and telecommunications expert in Israel—finally saw his creation vindicated by the British company Invicta Plastics. Based in the provincial Midlands city of Leicester, Invicta had been founded after World War II by plastics specialist Ted Jones-Fenleigh, who had used his Royal Air Force gratuity to start the company, which also released a range of other board games (and in 1974 began producing a line of museum-quality dinosaur models in conjunction with The British Museum of Natural History—the first of their kind).

Mastermind was eventually released in 1971 (during the Leicestershire UFO flap, curiously) and went on to sell vast numbers around the world—allegedly in excess of 50 million sets. With its glossy, primary-colored pegs and utilitarian grey plastic board, Mastermind resembled a piece of high-tech equipment, and, for some of us at least, possessed as much appeal as an artifact as it did as a game. In the original version, gameplay involved one player using those colored pegs to create a hidden four-piece code, which player two had ten turns to crack, each turn being scored with black or white pins that indicated how close the guess came to the target (similar to the iconic Battleship game, which goes back to the 1930s). While the game’s code-breaking theme kept owners more or less amused (in my own case, at least, Mastermind worked better as the instrument panel for imaginary spacecraft, actual playing of the game requiring levels of concentration and logic I totally lacked), perhaps the most striking thing about Mastermind was its packaging.

The cover of the original U.K. version described above was the one that defined the game in the imaginations of a generation. The two people featured on the cover, however, were not, in fact, an oligarch and his consort, but Bill Woodward—the owner of a chain of local hairdressing salons who lived near the Invicta Plastics factory—and Hong Kong-born Cecilia Fung, a computer science student at the University of Leicester who had been approached on the street by the agency organizing the shoot. Fung recalled that the dress she wore in the picture was so large that somebody had to lie on the floor behind her while the photo was taken to hold it tightly enough together to give the impression that it fitted, while Woodward (who the portrait turned into something of a national celebrity at the time, and who made the unlikely claim that his passport actually bore the name “Mr. Mastermind”) said that he was originally supposed to have been sitting, Blofeld-like, with a cat in his lap, but that the idea was scrapped after he was soaked with feline urine.

The cover of the original U.K. version described above was the one that defined the game in the imaginations of a generation. The two people featured on the cover, however, were not, in fact, an oligarch and his consort, but Bill Woodward—the owner of a chain of local hairdressing salons who lived near the Invicta Plastics factory—and Hong Kong-born Cecilia Fung, a computer science student at the University of Leicester who had been approached on the street by the agency organizing the shoot. Fung recalled that the dress she wore in the picture was so large that somebody had to lie on the floor behind her while the photo was taken to hold it tightly enough together to give the impression that it fitted, while Woodward (who the portrait turned into something of a national celebrity at the time, and who made the unlikely claim that his passport actually bore the name “Mr. Mastermind”) said that he was originally supposed to have been sitting, Blofeld-like, with a cat in his lap, but that the idea was scrapped after he was soaked with feline urine.

Over the years, the game was released in a bewildering number of variations (producing such contortions as “NEW original Mastermind”), but that original box cover—loaded as it was with social, economic, racial, sexual, and generational tension—set the model for the increasingly inscrutable iterations displayed on the game’s many subsequent U.K. and foreign editions.

After appearing in another photo used for the covers of Super Mastermind, Electronic Mastermind, and Super Electronic Mastermind (Woodward looked slightly less antagonistic this time around), Cecilia Fung’s contribution to Mastermind ended. Woodward, though, continued to appear on covers over the decades that followed: on the cruciform, four-hole Family Mastermind, he looms over the well-lit table, his fingers once again steepled and his checked jacket and jazzy tie placing him firmly in the mundane middle-class world; like a ghost ignored by the youthful players, he gazes confusedly at the viewer, bereft of all mystery. And yet an altogether more charismatic picture of Woodward, wearing the same jacket and tie and thus taken presumably from the same shoot, appeared on the cover of 1972’s Mastermind 44 (another cross-shaped game, though this time with five holes), gazing amusedly at his audience, behind him another exotic beauty wearing a red dress and regarding us ironically.

Woodward also appeared on the cover of one of the two versions of 1974’s Grand Mastermind—where the four elements composing the code consist of a color and a shape—now standing over a pair of exotic beauties, though here looking distinctly uncomfortable and lacking the stately hauteur of his initial appearances. He appeared particularly old-fashioned when compared to the altogether more thuggish-looking type—clad in a flashy blue velvet tux, standing rakishly in the same pose and against the same regal background with one of the same models—who dominated the second version.

Royale Mastermind (1972) presented a surprisingly sleazy new twist on the Mastermind aesthetic, with its image of a seedy playboy imperiously dictating the play from his sofa to two women kneeling on the floor. This machismo-drenched vision of the game, which by this time possessed a distinctly commercial aura, was strangely at odds with the campy disdain of the original box, and the roles of the two women here seem almost subservient, a million miles away from Cecilia Fung’s coolly appraising gaze.

Confusingly, given the country’s reputation for libidinousness and licentiousness, the two variant covers of the French version of Mastermind (see here and here) opted to do without women entirely, presenting a suave male player and implying an intimate masculine tête-à-tête without the distractions of sexuality.

The Brazilian version of Mastermind was sold under a different name altogether—Senha, or “Password”—and took a radically different approach to the franchise: the protagonists are still a man and a woman, but here we are worlds away from the urbane metropolitans familiar to us: the character on the cover looks more like a seedy private dick or undercover policeman, while the woman looks nearly bohemian.

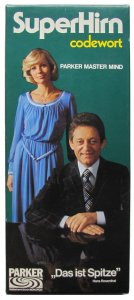

One of the various editions released in Germany—where it was known as Superhirn, or “Superbrain”—featured Hans Rosenthal, one of West Germany’s most popular television presenters of the 1970s and 1980s, who declared on the cover, “Das ist Spitze” (“It’s great”). Behind him stood Monika Sundermann, the hostess of Dalli Dalli, the quiz show on which they appeared together, and although the two respect the original’s seated-man and standing-woman format, the picture breaks with Mastermind visual tradition by having Rosenthal and Sundermann both wearing entirely unambiguous expressions and looking directly and frankly at the viewer. A later German version (1976) featured a colorful illustration of an older gentleman clearly intended to represent Albert Einstein.

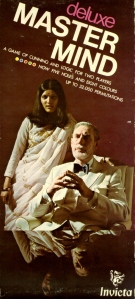

The 1975 release Super Mastermind (a.k.a. Advanced Mastermind, Deluxe Mastermind, and Ultimate Mastermind) featured another riff on the original design, this time with the aloof jetsetter replaced by a white-suit-clad gent who resembles a fusion of Colonel Sanders and some glacial Mittel-European technocrat. Behind him stands the obligatory female companion, this time of South Asian appearance and clad in a sari, a bindi on her forehead.

Of all the various covers, those of the Polish editions of Mastermind are perhaps the ones that break most with the paternalist, imperialist and implicitly sexist dynamics of the original and seem to propose a partnership, some measure of equality. Released by Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza, the first shows a couple of similar age, both clad entirely in denim: he, fingers steepled (natch), stares savant-like into space, lost in concentration, while she, a reassuring hand upon his shoulder, gazes frankly into the camera, her pose and long denim coat making her look more than anything else like a scientist, or perhaps the man’s trainer or handler. On the cover of another Polish variant, the man, fingers inevitably tented, seems to be assessing our chances as opponents, while the woman, clad in an elegant burgundy dress, her posture hinting that she is as much a participant as he is, also appears to be sizing us up.

The Dutch Mastermind Superieur also did away with the power inequalities that characterized the original, presenting us with a couple—he clad in a Bond-like white tux and she more informally in a low-cut vest and red blouse, both looking at us invitingly—who resemble professional gamblers.

Italy, for reasons known only to the marketing experts at Milan’s EG games, decided to forego not only the cover image but also the beautifully crafted pins themselves, replacing them with, respectively, a cartoonish illustration that wouldn’t have looked out of place in the 1960s, along with domestically produced game pieces wholly lacking the heft and allure of the originals, with a punctured paper tray in place of the plastic board. The name of the game was also changed to Codice Segreto—”Secret Code.” This was followed by a version that did feature a plastic tray and a photo cover, but one that offered little of the frisson of the Invicta original, depicting as it did a couple of healthy youngsters enjoying a productive and stimulating recreation session, as per pragmatic local tradition—though around the same time, presumably thanks to the labyrinthine licensing laws of the day, another company called IDG was selling the original Mastermind, relegating the mysterious couple to a small corner of the bright red box. An Italian version with the original cover did eventually surface, produced by obscure joint venture Invicta Bero.

Seen together, the covers themselves seem to present some inscrutable code. What exactly do they communicate about the contemporary societies of the countries in which they were sold? From this distance in time, what the various shifts in ethnicities and aesthetics imply—apart from in the most obvious cases—is hard to judge, though given what we know about the circumstances surrounding the original box, the idea that it might simply be representative of whichever vaguely enigmatic-looking man and attractive “exotic” woman Invicta’s photographers could get their hands on at the time seems fairly likely. The pictures of Woodward over the years give the game a peculiarly Dorian Gray-like property, as he mutates from the scornfully intimidating challenger of the early ‘70s to the harmless-looking avuncular gent of later years, more provincial granddad than Masonic Grand Master: on the cover of the 1979 Disney version, he is even seated in a wicker chair, clad in a safari jacket while he beckons amicably to Mickey Mouse and friends.

Mastermind is still sold today, though now packaged in a riot of abstract bright colors that screech “toy,” all traces of its previous incarnations—rooted in ideas of success and power that have shifted hugely since the game first appeared—now erased. In fact, the very idea that a game like this—or perhaps even an un-ironic tabletop game in general—could today be marketed to adults at least partly on an aspirational basis seems in itself pretty far-fetched. Perhaps, as well as telling us that we have made some small progress in moving past the chauvinistic, post-colonial vision of the world implicit in the game’s original cover, it also tells us that we have lost some sense of participating in events and that our naive faith in having a chance at taking on the big boys, even in as silly a form as a guessing game, has given way to an unspoken acceptance that the machinery controlling our world is so complex and manipulative that we have abandoned any hope of besting them, even in play. Or perhaps it is that the antagonists of today’s world are so faceless, or so horrendous—or both—that we would rather not see them at all.

Special thanks to Board Game Geek for most of the images used in this article.

![]() Richard McKenna grew up in the visionary utopia of 1970s South Yorkshire and now ekes out a living among the crumbling ruins of Rome, from whence he dreams of being rescued by the Terran Trade Authority.

Richard McKenna grew up in the visionary utopia of 1970s South Yorkshire and now ekes out a living among the crumbling ruins of Rome, from whence he dreams of being rescued by the Terran Trade Authority.

You do realize the first Polish image attached is not Polish at all? This one: https://granapare.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/dscn1854.jpg

It seems to be Croatian or another language (I can’t tell, I’m Polish, so I just know it’s not Polish 😉 ) Maybe it was released by the same publisher, but the text is not Polish, so even if it’s done in Poland it’s not for the Polish market.

Hi Dona – I think it might have been that it was the only high res version available of the image that originally appeared on the Polish version, but I’ll check. In the meantime, dzięki for pointing it out!

I have a gold, retractable ballpoint pen of early 1970’s vintage with the script, “Mastermind. The world’s greatest game” inscribed on the barrel. Were there any versions of this game that included a pen? I vaguely remember it being in the game box, but being too young to enjoy the game and just old enough to appreciate the pen. That’s probably how it got separated.

Hello Richard, I just bought a vintage version from Parker Brothers and my friend and I wondered about the marketing significance of the cover. Did a quick google search and found your excellent article. Thanks for this information. I’m actually going to print it and put it in the box!

Thank you, Sunny!

Here’s an archival link for the reunion article that you linked, since it’s no longer available at the given URL: https://web.archive.org/web/20160226151044/http://www.le.ac.uk/press/press/landmarkreunion.html

Pingback: Les origines mystérieuses du Mastermind - Gus & Co

Pingback: Non-Halloween Songs for Halloween